Pharoahe Monch released his fourth album—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In the album, Monch highlights the intersections of the stresses of inner city life, drug use, suicide, and the structural and cultural barriers to pursuing mental health care. PTSD just might serve as the perfect opening to a conversation on African American mental health.

PTSD follows Monch’s third album, W.A.R. (We Are Renegades). WAR was more of a metaphorical concept album that featured Monch performing from the perspective of an independent rap artist waging a war within and against the corporate music industry. PTSD marks Monch’s symbolic return to “civilian” life after his traumatic battles with the recording industry.

‘I went to the dentist and had to fill out forms and list all of the medication that I was taking. The doctor came out and called me in to his private office and told me that he didn’t mean to pry into anything, but he was going over my list and noticed the combination of my medications. He then informed me that one of the side-effects of a certain one included severe depression. As he said that, I melted into the chair I was sitting in and a thousand monkeys jumped off of my back. I started bawling right on his desk. I hadn’t put it together before that point…*

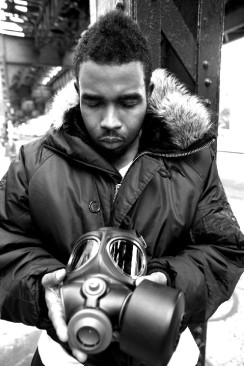

Several songs on PTSD address Monch’s experience with prescription drug-induced depression and his suicidal thoughts. On “The Jungle,” Monch references the list of drugs he’s taken to treat asthma: “I’m talking epileptic episodes off that Epinephrine, that Albtuterol and them other prescribed medicines, a zombie in insomnia freaking the Amphetamines.” Monch reflects on his suicidal thoughts on “Losing My Mind” and the title track, “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.” The artist contemplates on “Losing My Mind,” “No Medicaid, no medication. Thinking you’re better off dead. Instead should’ve been dedication to education. I spin, the cylinder on my revolver, I spin, the cylinder…” Monch’s suicidal thoughts are also evident on the album cover, which depicts him holding a gun to his head while wearing a gas mask. When reflecting on his darkest moment, Monch stated,

It’s true. You go to friends and family and people are like, ‘Fuck it.’ You just need to go get some help and shit.’ At the time, I was confused and befuddled on what happened all of a sudden, and I couldn’t put my finger on it. Cats ended up coming to my apartment and taking things away from me. They told me that I seemed to be going through some things and that I shouldn’t have these weapons around.

Monch’s reference to the lack of access to Medicaid on “Losing My Mind” points to another underlying theme—the racial and economic barriers to pursuing mental health care, especially for African Americans. “My family customs were not accustomed to dealing with mental health. It was more or less an issue for white families with wealth,” Monch raps. According to the 2012 National Healthcare Disparities Report, a little more than 50% of African Americans who endured a major depressive episode received treatment whereas close to 75% of whites received treatment. And between 2008 and 2010, white American adolescents and adults were more likely to receive treatment than African Americans. Monch’s observation about Medicaid also highlights the political barriers to affordable access, especially for African Americans. In an effort to resist implementation of the Affordable Care Act, Republicans in twenty-one states have blocked expansion of Medicaid. Several of the states where Republicans have resisted the expansion are located in the South—Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, to name a few.

Where States Stand on Medicaid Monch also points to cultural impediments to explain why many African Americans refrain from talking about their mental health openly. African Americans, especially black men, are often expected to endure the depressive episodes arising from life’s difficulties without medical or psychiatric help. “Tough” black masculinity requires black men to confront stress triggered by daily social, economic, and political struggles without showing any signs of emotional and physical “weakness.”

Bad MF produced by Lee Stone is the first look from this highly-anticipated fourth solo-LP, “PTSD” (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Pharoahe Monch re-emerges with a new concept project which finds the ground-breaking emcee tackling PTSD; a severe anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to any event that results in psychological trauma. Throughout the duration of the LP, Monch narrates as an independent artist weary from the war against the industry machine and through the struggle of the black male experience in America.

Find more information @ http://www.pharoahe.com/

http://nursingclio.org/2014/05/06/hip-hop-breaks-silence-on-mental-health-pharoahe-monchs-post-traumatic-stress-disorder/