Moolaadé focuses on Collé, the female protagonist who protects four girls against female excision (or female genital mutilation to be more accurate) carried out by the Salindana; a group of elderly women who perform the ‘operation’. Moolaadé itself is an ‘order of protection that holds a magical potency’ (Nochimson, 2012:4). It is Collé alone who can lift the Moolaadé if she is to “utter the word”, thereby lifting the protection and allowing the Salindana to take the girls. Collé sings and dances as she, and the other women of her compound, celebrate the first victory over the village elders when the Salindana fail to take the four girls from Collé as she refuses to lift the Moolaadé. We thus witness the first victory, or the first step towards liberation, beginning in one home from which the struggle spreads beyond as the narrative develops. The setting of the film is presented as a typical rural African village, perhaps to signify its ordinariness, its likeness to any other rural African community. These factors are significant because ‘Sembene insisted on individual choices, proactive choices anchored in the familiar, the banal, that could lead to exceptional moments of change in the everyday’ (Lindo, 2010:123). Indeed there is nothing out of the ordinary about the conditions from which resistance takes root, nor about the protagonist and second rank wife who decides herself to lead the resistance.

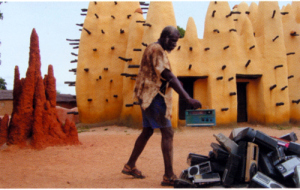

Defying the village elders, Collé is whipped in public by Ciré, her husband. We hear the men yelling “Harder”, “Utter the word”, juxtaposed with the women on the other side shouting, “Don’t say it”, “Don’t fall”. We also see the Salindana supporting the men. Furthermore, it is the male figure of Mercenaire who stops the whipping, ‘by defending a woman publicly, he diminishes the authority of the elders, challenges traditional practices and values, and betrays the male solidarity that sustains the elders’ authority’ (Lindo, 2010:118). Consequently, the scene can be interpreted as more than simply the binary opposition of men against women, and can perhaps be understood as traditional values being pitted against a new movement championing more modern ideals headed by Collé. Collé can be contrasted to the Salindana and the male dignitaries who cling onto old ideas steeped in tradition while she, like the introduction of the radio into her culture that we see her often listening to, is similarly introducing alternative ways of thinking. Perhaps this is again indicative of the theme of tradition versus modernity because ‘the radio, in particular, is regarded as a propaganda machine that introduces new ideas into the village and is held accountable for Collé’s decision to challenge female circumcision’ (Lindo, 2010:118–119).

The radio, Mercenaire and the character of Ibrahima, are all emblematic of modernity in this village where news travels by the beating of a drum. Significantly, all three support the female’s liberation. Nochimson claims: ‘This tension shows a way in which the absolute rule of men is threatened by the new availability in Djerisso of Western ideas, […] that have reached the village through the radio and through Mercenaire’ (2010:371–372). However, Sembene goes some way to ensuring that female liberation is not completely an external idea, supported by external factors. We hear Adjaratou mock Western girls “with hair down to their buttocks”, expressing a desire not to assimilate Western culture. Indeed, “Sembene often has harsh words to say about women who blindly imitate Western fashions’ Murphy, 2000:141). Also, the ‘everyday heroism’ of Collé further inscribes the notion of resistance as from within African society rather than it being frowned upon by the African viewer because it is presented as having been polluted by Western society. ‘The filmmaker is therefore aware of how the radio can also shape and diffuse images and ideas in progressive ways for his society’ (Lindo, 2010:119), but is careful not to overstate this and thereby neglect the role of the everyday African. Thus, Sembene films and writes with an African audience in mind, as oppose to a European or American audience. To corroborate this, polygamy is not criticised and perhaps deliberately by Sembene because ‘preserving institutions such as polygamy is seen as resistance against outside forces’ (Murphy, 2000:127). Presenting change coming from within African society is important because Moolaadé ‘seems explicitly intended to encourage indignation and, ideally, action’ (Porton & Rapfogel, 2004:20), and so it is necessary for Sembene to strike the right balance between modern forces acting upon African society as well as emphasising the ability and potential for progress coming from within this very society in the post-colonial era.

The reason for the burning of the radios by the men of the village is given by one of the women, Sanata, who states: “Our men want to lock up our minds.” As a result, men are associated with domination and power from which women struggle to escape. The radio and the television are forbidden in the village much to Ibrahima’s dissatisfaction as he argues, “We cannot cut ourselves off from the progress of the world.” Sembene therefore laments ‘the failure of the men of his generation,’ (Murphy, 2000:125) in fact, ‘Sembene has often spoken about his belief that post-independence Africa has been failed by men, and that women must thus play a leading role in any transformation of African societies’ (Murphy & Williams, 1997:61). The critique of male domination in Moolaadéworks to delegitimize both the absolute power of men and the misguided ideals that they adhere to, ultimately, Sembene is ‘casting women as a potent force within African society’ (Murphy, 2000:125) and cementing their place in the social arena in post-colonial Africa.

The reason for the burning of the radios by the men of the village is given by one of the women, Sanata, who states: “Our men want to lock up our minds.” As a result, men are associated with domination and power from which women struggle to escape. The radio and the television are forbidden in the village much to Ibrahima’s dissatisfaction as he argues, “We cannot cut ourselves off from the progress of the world.” Sembene therefore laments ‘the failure of the men of his generation,’ (Murphy, 2000:125) in fact, ‘Sembene has often spoken about his belief that post-independence Africa has been failed by men, and that women must thus play a leading role in any transformation of African societies’ (Murphy & Williams, 1997:61). The critique of male domination in Moolaadéworks to delegitimize both the absolute power of men and the misguided ideals that they adhere to, ultimately, Sembene is ‘casting women as a potent force within African society’ (Murphy, 2000:125) and cementing their place in the social arena in post-colonial Africa.

At the end, Collé is encouraged to confront the men, “Let’s put an end to female genital mutilations. This day will see the end of our ordeal.” As Collé addresses the men, a female griotte steps forward. The importance of this scene is signified by the presence of the original griot, who, traditionally, ‘is present at all major events to observe and preserve the history of the moment’ (Bouchard:57). The male griot watches on dumbfounded as the female griot chants praises, “Djerisso women, fasten your seat belts. You are more valiant than men.” Sanata, the female griot, is told to shut up as she is “from a lower caste”, another instance of Sembene promoting everyday heroism. The men’s responses seem irrelevant and the women’s movement seems to have emerged victorious over the ideologies of the male dignitaries. Here, Sembene is ‘in essence, attempting to create a “new griotism” for modern Africa’ (Bouchard:54), one that ‘upholds truth and justice in the face of moral corruption’ (Bouchard:53). Finally, Ciré leaves the men after hearing Collé declare that the Grand Imam said on the radio that female excision is not required by Islam. Ibrahima also leaves. These defections are significant as ‘Sembene’s everyday heroism opens up a participatory space in which both men and women can choose to come together to effect change’ (Lindo, 2010:121). Amsatou, the bilakoro, or “unpurified” daughter of Collé, approaches Ibrahima and he goes against the orders of his father by taking her as his wife.

The first event of this new society free of female genital mutilations. A new generation in Ibrahima, the King’s son, and Amsatou, are shown to do things differently. Amsatou vows, “I am and shall remain abilakoro.” Ibrahima smiles approvingly, suggesting that now, the female does have a voice and finally, in Ibrahima’s words, “The era of little tyrants is over.” The final sequence of the film shows the flames from the burning radios cloud the egg at the top of the Mosque. One could perhaps interpret this as modernity being presented as progressive and something that should surpass religion in post-colonial Africa because religion is to some extent presented as the reason for the views held by the men. On the other hand, perhaps religion is presented in a more positive light as it was indeed the Grand Imam on the radio who Collé referred to. From the egg on the Mosque, the camera cuts to an electric aerial, perhaps again stating that religion and modernity must coexist in post-colonial Africa, both have been influential in the triumph of women’s liberation.

In Moolaadé, Sembene is speaking for the woman, his ‘aim is to voice the resistance to domination that would otherwise have no public outlet, speaking out on behalf of those who are marginalised and oppressed, yet still defiant, within his society’ (Murphy, 2000:225). In this sense, Moolaadé continues a reoccurring theme in Sembene’s career whereby ‘the major ideological principle that characterizes his work is the recognition of the rights of women in society’ Gadjigo, 1993:1). Ultimately, Sembene ‘exposes women’s concerns to mobilize change in contemporary society as it configures new visions and ideas not only of women, but also of men’ (Lindo, 2010:112).

Nadeem Fayaz

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eUWSwJfz8gI[/youtube]

Download or stream online: http://www.africanfilmlibrary.com/Movies/Video/5078/465/Moolaade

Gata Malandra

Latest posts by Gata Malandra (see all)

- Event: World Crew Battle UK By Swatch — October 11, 2017

- Knowledge Session: Who Was Manco Inca? — May 4, 2017

- Video + Letra: Illmani ‘Saber es Poder’ — February 3, 2017