I walked into El Nido around 4 p.m., 2 hours after Jackson Turner’s memorial started. The front yard of the bar was unusually quiet and empty. A few people were hovering around the window that opens toward the stage. They were gazing at MC Webber, who was currently giving a memorial speech on the stage in a low, slow voice.

I walked into El Nido around 4 p.m., 2 hours after Jackson Turner’s memorial started. The front yard of the bar was unusually quiet and empty. A few people were hovering around the window that opens toward the stage. They were gazing at MC Webber, who was currently giving a memorial speech on the stage in a low, slow voice.

People were cramming together inside toward the stage. I have never seen the gathering of this many exuberant musicians and party-goers in Beijing being motionlessly silent in black, each mournfully reserved, and giving off a rare sense of solemn gloominess. The energy was heavy. Although I do not know Jackson very well, I felt the thick, chock-full sorrow in the room that drew me in toward him, and toward the contemplation of death.

Jackson Turner was “a hip-hop artist, an academic, a music technology entrepreneur, a producer, [and] always a seeker of truth” (“Jackson R. Turner” 2020). Each of these titles encompasses two sides of the world. One is New York, where he was born, raised, and soaked in hip-hop culture. The other is China, where he has spent two thirds of his adult life since 2003. He came as a student, and ended up a teacher and a reputable rapper. His presence in China was not only an influence to the local Chinese people musically and culturally, but also a uniting force for expat musicians from all across the world.

I first met him on February 4th, 2017, at Beijing Bob Marley Day Celebration. It was a reggae concert with a 20-year tradition. Jackson’s label and studio No Play Concept was the main organizer for 2017. The night was a combination of Raggamuffin, Hip-Hop and Reggae. The beat-driven, flow-centered, head-bobbing genre of raggamuffin is a subgenre of Reggae Dancehall born in ‘80s Kingston ghetto. The singer would be more or less “rapping” in Jamaican patois on top of a riddim, just like a rapper to a beat. During the 4‑act showcase in the celebration, three groups brought a Ragga-Hip-Hop flavor to the stage, delivering fusional Reggae aesthetics to Beijing audiences, a group accustomed to the city’s long favorite, Hip-Hop.

This very feature of fusionality I heard in the concert is a microcosm that reflects Jackson’s own music and beliefs. Musically, he enjoys fusion. He has a diverse music taste, which inspires him to inventively syncretize multiple genres into something he knows and loves the most. In an interview with Apex Zero, Jackson notes,

“My music has been influenced by a whole range of people from Nas to Eminem, to Bob Marley and Sizzla, to Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and Otis Redding. Even musicians far away from hip-hop, like Coltrane, Mingus, John Lee Hooker and Bob Dylan; they’ve all influenced me in various ways. I listen to all kinds of music and am constantly trying to learn and incorporate new ideas from other genres into Hip-Hop. This is how Hip-Hop began and, to me, it’s the spirit of Hip-Hop.”

One aspect of the spirit of Hip-Hop is fusion. It points to an open-minded inclusivity and an ability to catch the groove spot within all genres. This magical spot exists within everyone; it connects people. As Jackson envisions, catching the groove and fusing different music genres are ways to seek commonality of different people. It is a vision to connect different races into “distant relatives.”

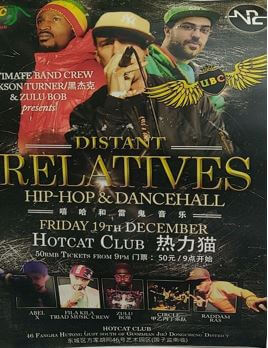

In 2014, he took this concept to French reggae musician General Huge and Cameroonian Reggae singer King Lion Miguel, hoping to start a series of fusion music events in Beijing. The series were named “Distant Relatives,” an idea found in Nas and Damian Marley’s eponymous album. Reggae artists, rappers and DJs would play together in the concert, bringing a mixture of Roots Reggae, Hip-Hop, Raggamuffin and Dancehall throughout the night. Rappers may freestyle on top of a riddim, backed up by Reggae musicians singing the chorus. Clashes between genres such as this brought surprises and inspiration to the performers. The stage was an intersection, a conference, a lab.

The first event was held in Hot Cat Club on December 19th. At that time, the tiny livehouse was still popping. The owner Li Lei, always dressed like a modern Taoist master, was a lover of Reggae. During that night, several things had happened. For one, it united Reggae listeners and Hip-Hop heads in Beijing for exchange and collaboration for the years to come. For another, Jackson introduced Raddam Ras AKA MC Webber, an O.G. figure in Beijing Hip-Hop, to General Huge. The meeting of the two had started a new wave of Hip-Hop-Reggae synergy.

The second event moved to a larger venue, Yu Gong Yi Shan, originally a discarded headquarter for the 19th-century Chinese warlord Duan Qirui. Both venues were opened by Chinese owners, and attracted large Chinese audiences as opposed to expats. This is something Jackson hoped for. As he states in the interview,

“Hip-Hop culture in Beijing is strange because it is extremely divided between Chinese and foreign Hip-Hop. The Chinese Hip-Hop heads are either creating their own underground music and performing it at live shows or they are doing the club thing. The foreign Hip-Hop heads are mostly involved in deejing and hype-man shit in the big night clubs. There are some people in Beijing who are trying to break down these barriers and make music and do events that involve both sides. I have always viewed this as one of my goals of doing music in China, though I have not always succeeded” (2016).

The main purpose of “Distant Relatives” was unity. Not only was it musical unity between Chinese and expats, but also one solely for expats who came from different backgrounds with unique cultural baggage and distinct styles. The DJs’ jobs were carefully planned out, according to General Huge, in which Chinese DJs play before midnight to a predominately Chinese audiences who prefer Roots Reggae, Dub and Jungle. In the latter half of the night, DJs with a Carribean or African background cater to a primarily foreigners’ dancefloor that favors the hot, body-shaking dancehall beat. Although slightly divided by time, the event pushes for the coexistence between different groups of listeners, and spreads awareness to a fusional aesthetics and existence.

An example: “Growing Up in This World,” Long Time Coming, 2017

Jackson was 34 when he released the album. He had been making music for more than 10 years, and this release was a cornerstone. The genres are diverse. The production team is multiracial and multicultural. Jackson’s project was a reason for them to get together and create. China, to them, transformed from a place to a space of gathering and creation.

“Growing Up in This World” is Jackson’s commentary on the troubles and struggles he sees in his home, America. It is a Reggae-Hip-Hop fusion in D harmonic minor, a scale that delivers a sense of melancholy, anxiety and solemnity. Throughout the verses, the drum plays an adagietto boom-bap beat in a raw and coarse timbre that resembles hitting on gasoline cans. Broken, fuzzy guitar chords spread in between the Reggae harmony on the up beat. The distorted electric guitar sounds create a sense of greasy crudity, recalling the image of the dark dirty streets of New York.

Jackson’s clear and nonchalant voice details the “American nightmare” (17) by providing scene after scene of toil and tribulation. “Ghetto teens on the block with crack rocks and stash spots / Trying to eat and increase their back pocket / Ain’t no laptops, pools or backyards / Just concrete, steal bars and gat wars” (18–21). “At your local Block Buster / You knocked up a fast little cock-loving chick with no condom on / Now you gotta deal with child support / And the cycle continues, trapped like a dying dog” (26–9). Jackson’s legato and narratory flow produces a concerned yet detached tone. It is a state consistent with his life track at the time, a New Yorker in Beijing, searching for clarity and answers from the East to solve his confusion and consternation about his homeland.

But he seems painfully discouraged. The chorus follows a downward melodic motion, as if a balloon is slowly deflating, expressing a sense of falling. “Growing up in this world of enormous extremes / Separated by nation but together we bleed / Every struggle within reaches a point of release / Rather die on my feet than have to live on my knees” (1–4; 30–4; 59–62). He sounds like the ultimate tragic hero, the wailer, the joker, the me-against-the-world loner singing the songs of redemption. After the second chorus, the keyboard riffs for a few bars in a fast yet sorrowful approach, creating a delicately flowing sensibility in a manner mimicking the sound of bleeding.

A fusion of genres symbolizes a fusion of two mentalities. Reggae mentality strives toward high hopes, and inspires the original Iyaman in the soul of us all. On the contrary, Hip-Hop aims to reveal the dark side, to purge the anger and pain in order to purify. The combination of the two expresses our common human predicament, a situation where one is stuck in between heavenly pursuits and earthly struggles.

This is also Jackson’s struggle. The rapper-turned-scholar was getting into a lot of troubles in the U.S. before 20, which was a major reason for him to move abroad (Apex Zero 2016). These early troubled times also shaped his views toward the world and toward politics. “I personally was arrested and expelled from high school over a rhyme I had written and this gave me a strong sense that the powerful will persecute people who they cannot control” (2016). This anti-establishment perspective is a core thread in Hip-Hop in particular. For the same reasons, Hip-Hop is commonly associated with violence, dissidence and irrationality, largely untolerated by the orthodox.

On the flip side, Jackson was also a philanthropist, a lover, and a seeker of wisdom. Positive threads found in Reggae ideology can also be found in many of his works. A recent release in Madarin, “One Love,” expresses this aspect. “No matter rich or poor / Put down your pain / Peace upon all / For my brothers One Love” (2018). Similar releases include “Music Souljahs” (2017) with Apex Zero and MC Webber, as well as a collaboration with General Huge, “The Foundation” (2015), described by Huge as the best song on love.

However, the spiritual-political movement behind Reggae, Rastafari, does not receive much appraisal by the conventional majority in Jamaican or the rest of the world. Rastas believe much of the world we are living in is the degenerated, corrupted and oppressive “Babylon.” Listening to or making reggae music along with the practice of a natural and self-sufficient lifestyle are seen as positive cultivations that heal and protect them from Babylon. In the eyes of the “Babylonians,” however, many Rasta practices were heretical. For example, locs, the Rastas’ symbol of resistance against the mainstream’s norm of the smooth and artificial hair, is often incorrectly considered as dirty and bedrugged. Those who wear locs are still often treated as lower than those who wear straightened or combed hairstyles. Compared to the typical or stereotypical office worker, Rastas are the outcasts, the bandits, the heretics.

Heretic. That’s it. Jackson chose this word as his MC name. He also had a tattoo of it on his back in large, Arabic-styled font, described Balang, Jackson’s close friend since 2005 as well as a local Hip-Hop head and basketball player. The two met on the campus of Capital Normal University. At that time, Jackson was a language student, fresh off the boat. Balang was the son of a music professor and lived in the area since he was a kid. Jackson lived in the international student hall, always wearing a pair of Timberland boots, gray sweatpants with an XXXXL Give Me Face vest. He caught Balang’s eyes a few times, and the basketball player finally decided to talk to the rapper in 2005 on the stairs of the international student hall.

That conversation lasted for about two hours. Balang was amazed at Jackson’s language skills, because not only could he speak Chinese, but he was also a master of the tone, the style and slang. They talked about Hip-Hop. Jackson was a fan of the New York group Dead Prez for their politically conscious lyrics, and he even recited one of their songs for Balang. They talked about movies. From then on, Baland would go to Jackson’s dorm and watch movies with him. Charlie Kaufman. Synecdoche, New York. David Lynch. The Lost Highway. Blaxploitation comedies. It’s Who’s the Man. To Balang, Jackson was a treasure box, always having something cool to show him. He paved a way for Balang to understand Hip-Hop more in-depth and diverse, and also showed him — and his friends — a Hip-Hop mode of being by embodying the culture.

Before he came to China, Jackson looked up to Shifu Liu, a Chinese revolutionary and advocate for the Chinese Anarchist movement in the 1910s. Compared to most socialist thinkers at the time, Shifu started off as an extremist, supporting revolutionary terrorism and assassination of criminal elites. Later, these heretical ideas developed into more acceptable approaches, such as forming “an alliance between intellectuals and workers” (Dirlik 1993: 117), and asserting rights for oppressed groups in China.

As a young thinker fascinated with Eastern teachings and alternative governments, Jackson felt the connection with Shifu. Both thinkers resisted Babylonian society and politics, and sought out different ways to bring about change. Jackson told Balang how he felt the pain when he read that Shifu’s arm was blown off in a confrontation with oppressive powers, and how he wanted to wipe out those who bombed Shifu. He knew such thought is rendered heretical — he knew as early as in high school when he was expelled for his lyrics that expressed similar ideas.

Jackson travelled to Shifu’s tomb in Hangzhou twice between 2005–2008. He could not find the hidden and abandoned tomb the first time, and the second time took him many twists and turns in the woods. “Jackson is very emotionally-rich,” commented Balang. “He can hear the overtone of sounds. He is just like how Su Dongpo described, ‘the passionate one is always hurt by the ruthless.’ ”

Jackson Turner, the heretical one, had left his mark in China. Eventually, he left the world like a rock star — in a swimming pool on vacation in the back garden of America, Mexico. But perhaps he never left us, as General Huge comments. He just transcended to a happy place and decided to stay there.

Written By Meng Ren

Guest Author

Latest posts by Guest Author (see all)

- ‘TODAY’S HIP HOP IS TOMORROW’S RELIGION’ BY ABSTRACT BENNA — January 23, 2022

- POETRY | ‘DIAMONDS WITH HIS BARE HANDS’ BY JAVON RUSTIN — January 4, 2022

- REMEMBERING JACKSON TURNER, MC HERETIC — October 26, 2020