“Words are more treacherous and powerful than we think” (Jean-Paul Sartre)

Since the beginning of time words have been the world’s most potent weapon. They can be a source of comfort, of battle, and both equally a divider and a unifier. To many it would appear that hip hop, that is, the art of using the spoken word over a back beat, is a more recent phenomena, and particularly within pop culture had only had not long ago burst onto the scene. But this widely held notion, one that views hip hop as having emerged in 1970s New York, is historically, politically, and philosophically, pure mythology. It can be traced through disparate musical traditions right down to the African griot traditions of West African empires. This demonstrates what a powerful and misunderstood art hip hop really is. When we view it in this way, through the lens of its real, rather than assumed history, we can take it away from the stereotype of rap. That is, the young misogynistic black man speaking of bitches, money, and displaying greed and wealth. While there are many willing to propagate this image, so much so that British rapper Akala once called rap “the misogynistic, materialistic handmaiden of American capitalism”, there is a richness within hiphop that is deeply reflective, conscious, diverse and sadly hidden in the underground.

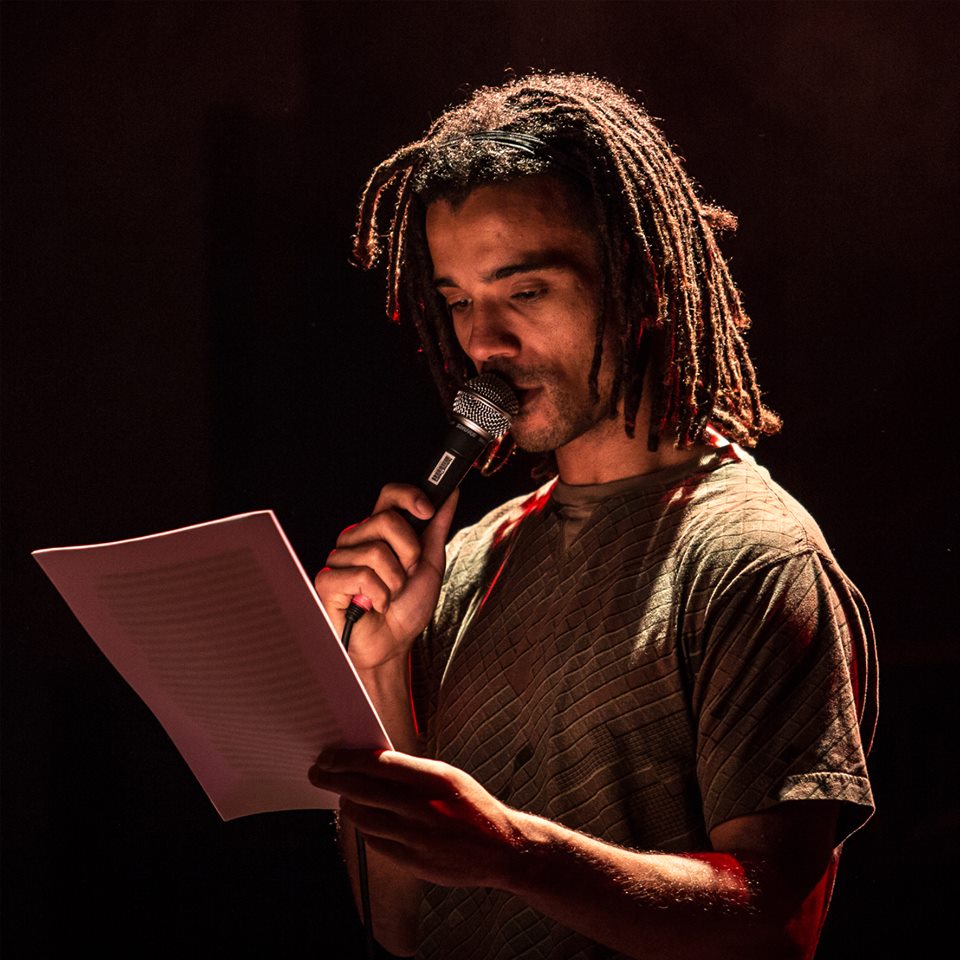

Credit: Akala Official Facebook

It is important to remember that hip hop was conceived with a purpose. That purpose included resistance to oppression, breaking down stereotypes and barriers, not to accept the norms imposed on you by society depending on your social status or ethnicity. Ultimately, it stood, and still stands, to be the voice of the voiceless. And this is where we can begin to draw parallels with other means of expression. Similarly Wallace Steven’s, an early 20th century poet, once described poets as being “the priest of the invisible”

For many, the ultimate draw of hip hop is in its lyricism. Words are the key to its power. And what many sadly fail to hear is the wonderful world of words which some artists create. The articulate, the conscious, the rappers still fighting injustice are not always heard. Those artists to me, people like Akala, Lowkey, and underground acts such as Phoenix Da Ice Fire, plus those better known like Dead Prez, Eminem, Kendrick Lemar, are both intellectuals and poets. Many may lack “mainstream education” but education and intelligence are far from the same thing. According to the philosopher Albert Camus: “An intellectual is someone whose mind watches itself”. All the aforementioned rappers do precisely that. They describe both their internal and external reality in a way that many with a phd would struggle to do.

There is also no doubt that we can call some of these rappers ‘poets’. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a poet as “a person possessing special powers of imagination or expression.” Sounds familiar? For William Wordsworth, a 19th century poet: “Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings. It takes its origins from emotion recollected in tranquility”. That a quote two centuries old resonates so clearly in that it describes many artists we have mentioned, we cannot disband the notion that good conscious hip hop is most definately poetry. We have already made clear that hip hop’s main role was, and still is for many, to break down barriers. Robert Frost, the great American poet at the beginning of the last century once said that “writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down”. Conscious hip hop aims to do just that, pull down whatever stands in its way and just let go.

So it is of no surprise that a hip hop artist, seeing the similarity between his and fellow artists work and that of historical texts decided to devise a scheme to encourage young people to engage in these historical works that they felt had no relevance to them. In this instance, it was Shakespeare. The artist in question, Akala, has a track called Shakespeare and it is from this basis that he decided to take the whole concept a step further.

Akala, real name Kingslee James Daley, was born in London in 1983. His stage name is a Buddhist term for “immovable”. He began his recording career in 2003, released his first album ‘It’s Not a Rumour” in 2006, and once daubed himself “the black Shakespeare”. It is on this basis that he launched himself into an educative role, aimed at using his skills to immerse young people into the work of the likes of Shakespeare.

Firstly he set up the The Hip hop Shakespeare Company in 2008. “Both hip-hop music and Shakespeare’s theatre represent energetic and inventive forms of expression. Both are full of poetry, wordplay and lyricism. Both deal with what it is to be human, and issues from people’s lives, and of course just like Shakespeare’s work, hip-hop is all about the rhythmic tension of words. The similarities between hip-hop music and Shakespeare’s theatre are striking. As a media-savvy popular entertainer and talented businessman, we think hip-hop would have been Shakespeare’s thing – a truly old-school Jay‑Z.”

Akala notes that both hip-hop music and Shakespeare’s have been misrepresented in that hip-hop is not given the “intellectual credit it deserves in an academic, literary or poetic sense”. At the same time, Shakespeare, he posits, is often presented from a culturally “high brow” viewpoint which for many young people makes his work seem irrelevant to their lives and therefore boring. He offers up writing workshops for young people, and has a touring theatre company that performs his adaptations of Shakespeare’s work.

His track, ‘Shakespeare’, states: “I’m similar to William, but a little different, I do it for kids that’s illiterate, not Elizabeth…. It’s like Shakespeare with a nigga twist… it’s william back from the dead from the dead, but i rap bout gats and I’m black instead”

Akala on his Hip Hop Shakespeare Theatre website declares that, “After rapping about Shakespeare in some of my songs I developed the moniker “the Rap Shakespearean” among the press and my fans. In 2008, I decided to look for ways to spread my own love of Shakespeare to other young people in a more structured manner….from which THSC was born.”

Towards the end of last year articles began appearing in the press concerning this comparison between Akala and the Shakespeare, this country’s most famous wordsmith. Typically this involved the most modern technology, a computer app, that highlighted the comparison between Akala’s work and that of Shakespeare. Created by the Royal Shakespeare Company in collaboration with Samsung, the notion was simple. It proffered up quotes and asked the user where the quote originated from, Akala or Shakespeare. Many failed to distinguish between the two. This surprised many who held the aforementioned stereotype of rap. But for those more aware of conscious hip-hop born from deeper roots, this was not news.

It may be a good idea in theory that by developing a “fun new app” to engage kids into learning historical texts via modern culture, we could encourage learning. And as Akala asserts so often, including in an album bearing this name, “Knowledge is power”. Quotes like. “Strange is the fruit that nourishes Not the bring, this is more than sophisticated savagery” sound pretty Shakespearian right? Wrong. It’s Akala. But for me, the project is lacking a dimension. The aim is to take pupils back in history. But it would be far more powerful if instead of using Akala as a key to opening another door, we also teach these artists in their own right as examples of modern day “poetry”. This is an era where young people need powerful intelligent idols in the here and now. History is vital to the way in which society is constructed, and how we construct ourselves in it. It contextualises everything. So yes, Shakespeare is, and always will be fundamentally relevant. But we also need to look at the here and now. Akala, for example can teach us about history. In his tracks he references various icons from Martin Luther King, to Malcolm X, to Bob Marley.

Photo Credit: Lowkey Official Facebook

Lowkey on the track Cradle of Civilisation takes us back through his iraqi heritage and the devastation of both Saddam Hussein and the subsequent American invasion on his “motherland” and the desecration of Baghdad. The stunning voice of Mai Kahill singing “Oh how beautiful is freedom” in Arabic is so incredibly beautiful, and his lyrics so powerful, that he again transcends stereotypes and can teach another side to people about that facet of politics and history, and it is a side we rarely hear. With each artist, we listen, and we learn. The death of his brother by suicide, expressed in “Bars for my Brother” teaches us the raw pain of loss.

Again, Mic Righteous in his BBC radio 1 Fire in the Booth session points to the political here and now, from the riots of a few years ago in English cities to those on a more global level: “there’s a war going on outside our doorstep…Pakistan’s an ocean, bodies in the brown water floating, people forget. As Syria falls apart, we watch the problems progress, when will it end?”. Again more teaching to be offered up from current events that may otherwise go missed by certain young people.

There are hip hop artists in Brazil, in Iran, in Gaza, in Israel, in fact in virtually every nation one can think of, bringing their own flavour through their own unique culture with them. The UK is no exception, yet many gifted artists such as Lowkey, have been shunned from the mainstream.

People have often pointed to hip hop as a dangerous force. Often quoted are the the rap wars that were highly prevalent in the United States especially in the 1980s and 90s and equate it with violence. Many still think of rap as being synonymous with gang warfare, especially that which erupted in the notorious east/west coast divide that is allleged to have culminated in the deaths of two of hip hop’s biggest names, Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur. And yes, there must be care from those in prominent positions. Social icons do have a big responsibility. After all, as Sartre also said, “Words are Loaded pistols”

But we can look at this through another lens. That rather than causing social problems, we can see hip hop as just an expression of them. It is an often brutal expression. But it is also a necessary one. It is a catharsis that allows those who might otherwise engage in violence, channel those feelings in another way.

Benjamin Zephaniah, the famous British poet, commented on why he wrote his novel ‘Gangsta Rap’: “I love Rap music. Many people say that teenage boys are not interested in poetry but Rap is simply street poetry. Why do kids get embarrassed when you call it poetry? I used to. I love poetry, but poetry reminds lots of kids of dead slow words written by dead white men. Rap tells it as it is. It might grate or upset you, but people who are studying youth trends should just listen to Rap music as that’s where it’s at. Rap is street poetry owned by young people. Nowadays every kid on a street corner is a rapper and that’s all good”

This collision of seemingly different worlds is becoming more overt. It’s been a long time since Ice T burst onto the rap scene in the 1980s. The one time “Cop Killer” singer has very recently begun to engage with the links between hip hop, poetry, and other forms of music like jazz. He was approached to narrate the live jazz-poetry piece Ask Your Mama, originally penned by poet Langston Hughes in the 1920s

When asked if he sees a gulf between his own experience of rap culture and the America inhabited by a gay, radical poet of the 1920s his answer again points towards the hidden intellectualism underlying contemporary hip hop.

“People may not associate rap with intellectuals such as Langston Hughes. But look at stuff from Public Enemy, KRS-One, Nas… it’s highly intellectual. Rap is like anything else: there’s some high-tech stuff that’s going on and there’s basic stuff too.”. Ice‑T performed this work at The Barbican Centre in London at the end of last year.

And what true hip hop lovers know inherently is being consolidated academically. In February 2015 Linguists from Manchester University revealed some findings from research that had been undertaken examining the work of hip hop artists. Examined were rhyming patterns, vocabulary size, rhyming structure. Imperfect rhymes, they say, do not come naturally, but they found for rappers they had become “second nature”. The Oxford English Dictionary credits Shakespeare with coining up to 2000 words we use today. But these linguists found that the likes of Eminem and Akala are more adept at creating poetry and prose than the 16th century poet. Louise Middleton, who conducted the research, quotes Rap God by Eminem, “For me to rap like a computer must be in my genes”. This, she says, supports her theory that rap is often outside conscious control

“I think that hip hop has the most sophisticated rhyme of any genre and when written down it reads like poetry” other research quoted suggested rappers have a better vocabulary than many scholars.

Jaqcui O’Hanlan RSC education director: “Shakespeare dealt with terrible, deadly, dangerous things through the most beautiful language” Language is power for hip hop artists and they use it to provoke, challenge and move people like Shakespeare did” Of course we must also recognise that there will always be differences given the context: “Every age has its own poetry; in every age the circumstances of history choose a nation, a race, a class to take up the torch by creating situations that can be expressed or transcended only by poetry” (Jean-Paul Sartre)

What may come of these apps remains to be seen. But it is encouraging that the world is waking up and starting to realise that within hip hop there is a powerful use of language, and a love for words that needs to be nurtured, not negated. And that can only be a good thing. For the first time we are entering an era where there is a recognition that hip hop can quell rather than cause the social unease it has been addressing.

Akala, at least, has been having fun with his games. In an interview in the Observer in 2013, he throws a line at the interviewer, “Sleep is the cousin of death”. Macbeth? the writer guesses. Nope, that one was from “Nas”. The next one, “Maybe it’s hatred I spew, maybe it’s food for the spirit”. The answer? Eminem. Finally, he offers up a simple reason why many may be confused, it’s “The same subjects and themes… just 400 years apart”.