Q. Your poetry covers a variety of topics from politics, social and history. Why do you think it is important to speak on these topics in particular?

Poetry for me has always been about exploring and excavating the human experience. To traverse through themes that range from political struggles to societal issues whilst bridging together certain historical epochs I guess is somewhat conducive to the overall purpose of poetry. As a writer I try to put little emphasis on themes. I don’t really like the idea of writing a ‘political poem’ or ‘love poem’ simply because the definitions of what political poetry should entail or what love poetry should entail are so delicately interlinked that it’s wrong to make an attempt at standing the two apart. For instance if I write a poem about a woman I love and in that poem I make references to unemployment or a class/race struggle, however nuanced it might be, then that automatically qualifies the poem as being political. Love when dissected properly can prove to be a highly political act, so in truth the best poetry will forever be entrenched in the most poignant themes of the human experience, irrespective of topic.

Q. When writing your poetry do you have a certain system that you follow for each piece or does it depend on the topic that you are writing about?

I’ve always felt that I’m somewhat of an organic writer. I’ve had no formal training in the art and craft of poetry, all my knowledge about technique, form and meter I’ve had to acquire through studying the great poets, by reading their work repeatedly, seeing how they manage to congeal abstract ideas with sonic dexterity and language creating one seamless piece of art. Again I think as a writer it’s important to remain as uninhibited as possible, and that means staying formless and unrestricted in both style and voice. Most of my work derives from a feeling, usually this feeling becomes so overpowering that I feel compelled to write, the same way some people feel compelled to talk to a friend or loved one when going through a difficult time. When I read back over my various collections I can see how it’s me who’s writing but then each poem embodies a different aspect of my character. It’s a bit like a person who wakes up each day to wear a new set of clothes, the body remains the same but what get’s put over it will always differ in accordance to the individual’s mood and feelings.

Q. For anyone reading this interview and thinking of starting to write poetry what tips could you offer them?

I think the most important thing for anyone writing or thinking of writing poetry is to first and foremost read poetry. When I teach young people in schools and I often get asked to give tips in which I always find myself going back to that same old line of it’s vital to read poems, to listen to poems and to think about poems if you’re to create solid, original pieces. I think everyone will agree with me when I say that there’s no way Hendrix could have been as great as he was if he didn’t listen to blues prodigies such Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and B.B King. In the same way Salvador Dali wouldn’t have been able to paint such controversial surrealist images if he wasn’t influenced by African surrealism. It goes on but you can see the point I’m making. The truth is most people are scared of poetry; I’ve always contended that schools do to poetry what the media does to Islam. Our first introduction is bland, misrepresented, rigid and grossly irrelevant to our every day lives (or so we’re led to believe) but the heartbreaking thing being that this couldn’t be further away from the truth. Poetry does not just consist of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Lord Byron and an antiquated consortium of other strange looking White men who speak in an almost cultish, archaic vernacular, poetry when elucidated properly is a genuine reflection of the human condition in all its dimensions and frequencies.

Q. Over the last few years we have witnessed demonstrations across the Middle East on a scale not seen before. In your opinion what were the main catalysts for these demonstrations and do you feel they have achieved their aims?

As with any form of civil unrest the main cause is always a break in the power-structure chain. In the Middle East as in South America and parts of Asia and Africa we have see time and time again that when people are reduced to dire living conditions, unequal job opportunities, overt discrepancies in the legality of voting and mass poverty, all will in turn boil over into an atmosphere of heavy protest. Regarding the Middle East and the Arab Spring we have seen a group of people finally standing up to Western settlement, neoliberal policies, British and US sanctions as well as a volley of other strategies and policies implemented by the West in order to maintain their economic control over the region. If the end result to any form of mutiny is that people are able to live at a more liberal means, with less oppression and less dictation from foreign authority then we can say that the cause was just and revolution regardless of its intensity is a much needed force in the battle for global equality.

Q. Throughout history there has always been governments and leaders who have profited off the death of their own or other people but since the emergence of imperialism this seems to have hugely increased, why do you think this is?

I don’t think the emergence of Imperialism has increased. The very idea has been around since time immemorial. We need to understand that Imperialism is simply the common ideology that accompanies an Empire as it moves into local or more foreign territories in their endeavor to control and subjugate the indigenous people. The real problem I find exists within in the multiple facets of Empire; predominately cultural and racial superiority, hegemony and the staunch effort to eradicate a peoples’ history and tradition so as to enforce something alien and ill-favored through the use of violence and decree. Leaders will always require a certain amount of objective scrutiny if they’re to be understood properly. There are and have been many nobel, socialist leaders who have risen to represent the proletariat but as the nature of politics reveals the good are usually removed by the crudest of methods by the majority who’s interest is steeped in prolonging and upholding the status quo, regardless of how pernicious and detrimental that might be to the future and stability of a nation.

Q. You recently travelled to Vietnam and Cambodia. Were there any experiences that have made you look at yourself and people in a different light?

Absolutely. It’s more or less impossible to travel to parts of the global south and not come back to the West with a difference in perspective. To witness poverty in it’s raw and desperate form is enough to leave any Westerner with a tattooed taste of guilt in their spirit. I met some incredibly beautiful people during my time there, all of which were mostly illiterate, living in corrugated iron shacks but yet possessed a sequential understanding of history and events. I can’t think of anything more horrific than living on less that $2 per day and knowing the West, as well as other internal factors, are the cause of all suffering. Cambodia is the poorest country in South East Asia which I found surprising as I presumed Vietnam to be due to the American war, however that atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge (in a country of 8 million 3 million were murdered in just under 3 years) have resulted in a very slow rate of recovery. Vietnam on the other hand is extremely anti-West (and quite rightly so) with a deep communistic national character and a healthy trading alliance with China. When you’ve seen and lived amongst a reality that is as urgent and serious as what theirs is, it becomes difficult to come back to the West and cheer on a football team, or concern yourself with the latest fashion trends or music fads. Our life in Britain isn’t perfect but when compared to the life of others all I can say is that some people have real problems.

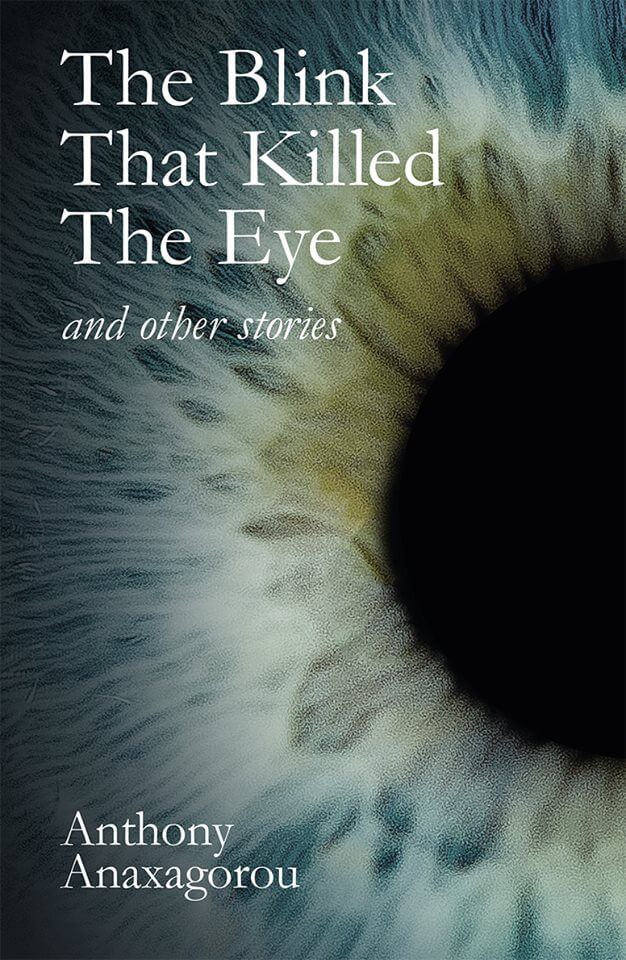

Anthony Anaxagorou new collection of short stories is available to buy from from all good book retailers and online.