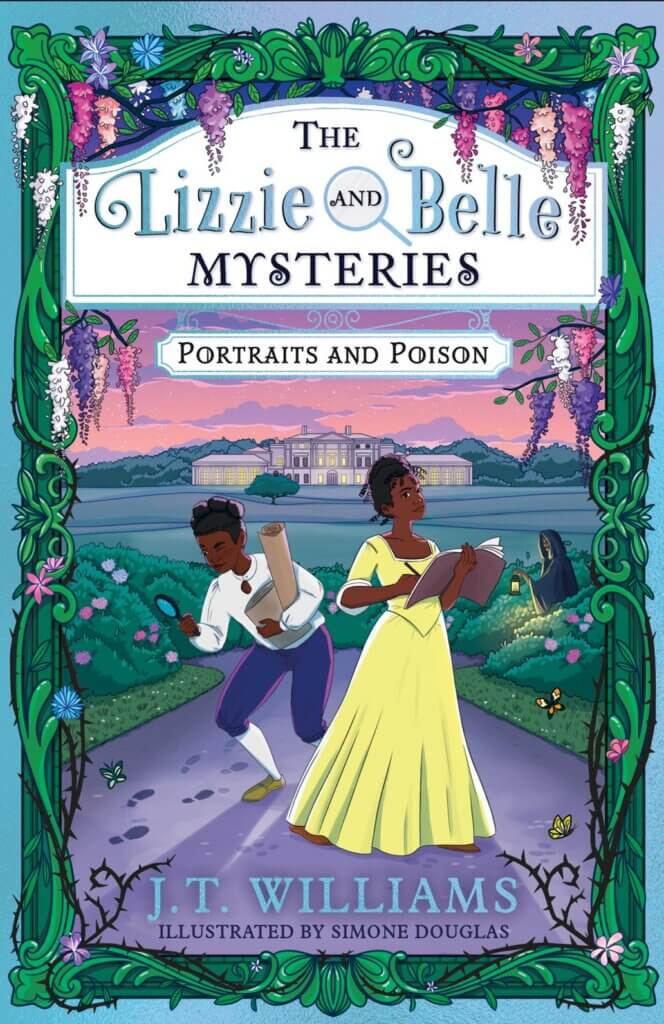

J.T Williams is the author of the Lizzie and Belle Mysteries series, which follows two Black British girls in 18th-century London as they solve mysteries and uncover the hidden histories of Black people in that era. Williams was inspired to write the series after discovering the intriguing life stories of Dido Belle and Ignatius Sancho and feeling compelled to make their stories more visible for younger readers. The series is aimed at middle-grade readers and balances compelling mysteries with relatable and engaging characters. The latest book in the series, “Portraits and Poison,” involves a complex mystery that touches on issues of power and privilege in 18th-century London. Williams’ work as an educator and historian is evident in her writing, which is both informative and engaging.

We catch up with J.T Williams on publication day of Lizzie and Belle ‘Portraits and Poison’ to learn more about her incredible journey.

What inspired you to write a mystery series set in eighteenth-century London and featuring two Black British historical figures?

History fascinates me. What new lessons can we learn from past lives? I grew up devouring novels written long ago, and I love watching a period drama on TV. But as a Black British woman, I always wondered where people like me were in those stories.

Later in life I discovered through my own reading and research that there were around fifteen thousand Black people living in London in the eighteenth century (out of a London population of around 650 000), but in films and TV dramas of those times, and later, we seemed to have been airbrushed out of the picture, or pictured only in the background, at the edges, in the margins.

When I saw the portrait of Dido Belle at Kenwood House, and later, the painting of Ignatius Sancho, and found out more about their intriguing life stories, I felt compelled to make those stories more visible for younger readers.

I wanted to shine a light on the Black Abolitionists who resisted slavery by rebelling, by running away to seek their freedom, by writing to expose the horrors of slavery and assert themselves as human beings deserving of respect. Those are the stories are children should be hearing about.

How did you approach researching the historical context for your book, and what challenges did you face in bringing this period to life for young readers?

The 18th century is not the most ‘familiar’ period in British history for younger readers, and the teaching of Black British history is still lacking. At primary school you learn about The Tudors, the Victorians, World War Two, maybe even the Vikings, but silence surrounds the Georgian era. I suspect that this is because this is the time when Britain was at the height of its slavetrading power, and that’s a story that is still being suppressed.

So the main challenge is — how to tell that story so that it is not traumatizing for younger readers? By having Lizzie and Belle as the guides through the story, I wanted to create space for young readers to have a moral response, and to have a sense of agency, by uncovering and challenging these crimes.

If we don’t talk about that difficult history, we risk losing all the other stories that come with it. Stories of Black resistance and resilience, of surviving and thriving, and even joy, love, familyhood, kinship and community-making.

You have to paint the settings in fine detail, to immerse readers in the environment: the streets, the houses, Sanchos’ Tea Shop. It all has to have a sensory power to draw readers in. What does it look like? What does it sound like? How does it feel to be running around those streets?

The Lizzie and Belle Mysteries series is aimed at middle-grade readers. How do you balance writing a compelling mystery with creating relatable and engaging characters for this age group?

Character is key. I wanted Lizzie and Belle, two bold and brilliant Black British girls, to form a friendship, a detective partnership, to solve the crimes they witness. Each girl has her own unique personality, her own skills and approach to detection.

It’s crucial that the girls tell their own stories. The Black girl’s voice had to be at the centre of everything. The first book, Drama and Danger, is written from Lizzie’s perspective, in her voice.

Lizzie is curious and courageous, direct and determined. She has street smarts from growing up in her family’s busy shop. She doesn’t have time for eighteenth century etiquette like wearing massive dresses, curtseying, or overly elaborate speech! So I took license with the language to give her a very direct, contemporary voice. I was thinking, what might a girl of today make of the eighteenth century if she were to go back in time?

Belle takes over the storytelling for Portraits and Poison: we get a deeper insight into her family life and how she handles her friendship with Lizzie. The challenges of friendship, family, these are constants of human life, whether now or 250 years ago.

In Portraits and Poison, Lizzie and Belle are faced with a complex mystery that involves a stolen painting and a conspiracy with links to the kidnapping of Lizzie’s friend Mercury. How did you go about creating the plot for this book, and what challenges did you encounter in keeping the mystery engaging for young readers?

Writing a mystery is complicated! It’s like putting a puzzle together: you have to know what your end point is before you get into the detail of how it’s going to play out. You’re intertwining a series of threads. For me, plotting involves lots of colour coding, lots of post-it notes.

For years I’ve wanted to address the issue of how Black people were represented in European art in the eighteenth century. Pushed to the edge or the bottom of the canvas, gazing up at a white subject, a tray of fruit or flowers in their hands. And those people were young — often children. So I had to challenge it. And bring those unnamed children to the centre.

I think the engagement comes from the emotional connection. Again, it is Lizzie who provides that beating heart for the book because she responds to situations with her gut, with her emotions. So I’m taking these historical situations and fleshing out the emotional impact they would have had.

Ultimately, the girls are discovering — and challenging — the corruption behind power and privilege. That’s a situation as relevant today as it was back then.

Your work as an educator and historian is evident in your writing, which encourages children to explore hidden histories. Can you talk about the importance of representation and diversity in children’s literature, and how your books contribute to this conversation?

We know that it is crucial that children see themselves represented in the books they read in order to feel they belong in the world and that they belong in the world of literature. I want to make visible that Black presence in Britain’s past, and do so in a way that can instil pride, that reveals the contribution we have been making for centuries to the health, wealth and cultural life of this nation. And that positive representation of Black communities is equally important for children who aren’t Black, too. They need to have a more rounded sense of Britain’s past: they also live in a diverse society.

Presenting a whitewashed world in literature is not doing any favours to any of our children. So now we all have a lot of work to do to undo that damage and make cultural material that restores our sense of pride, that invites us to hold our heads up high. Black Panther, The Woman King, these films have done that on a global scale. That kind of representation should run across all genres of story, for all our young readers: action, thriller, mystery, fantasy, sci-fi, historical adventure, family dramas, friendship stories…

The Lizzie and Belle Mysteries series is developed by Storymix, which creates pathways for UK BME authors and illustrators into children’s book creation. How important is it to have initiatives like Storymix in the publishing industry, and what impact do you think they can have on promoting diversity in children’s literature?

It’s crucial — I can’t emphasise it enough. So the stark imbalances and gaps in representation revealed by those Reflecting Realities reports (CLPE) are due to poor representation in the publishing industry. That goes for writers, editors, agents — Black people are underrepresented at all these levels, so of course the books coming out are going to reflect that. At the beginning of Drama and Danger, the first book in the series, Lizzie says, ‘Until the lions have their own storytellers, the story of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.’ She says that ‘if we don’t’ tell our own stories, someone else will do it for us, and if we let them do that, how can we trust them to tell it right?’ Until more creators of colour have a genuine foothold in the industry, we need initiatives like Storymix to bring our stories to the centre, and to create beautiful and brilliant Black characters for children — all children — to read about.

What advice do you have for young readers who are interested in writing their own stories or pursuing a career in writing?

Keep reading, keep listening, keep writing! Read your work aloud during the process — after every sentence if you like! — to see how it sounds. And edit, edit, edit. Your voice will soon come in the sound of it. Remember that inspiration comes from everywhere: it might be music, films, daily experiences, friendships, family. I have written diaries since my teen years. It’s great practice for expressing your thoughts in written words. Get together with friends who love writing — hold showcases amongst yourselves, read your work aloud to each other. Tell the stories that are important to you.

Finally, what can readers expect from the next book in the Lizzie and Belle Mysteries series, and what are your plans for future writing projects?

I definitely have more ideas for The Lizzie and Belle Mysteries in the bag. My research keeps throwing up more and more surprises — watch this space!

I’m also writing for adults at the moment and working on some fascinating family history. The stories of our own families can often be the most intriguing when it comes to discovering history.

Ultimately, I’m grateful that I get to read and write every day. There are many more stories to come, believe!

Mark Mukasa

Latest posts by Mark Mukasa (see all)

- INTERVIEW | SELINA BROWN ON FAMILY, FOOD AND CULTURAL PRIDE IN HER NEW CHILDREN’S BOOK ‘MY RICE IS BEST’ — April 28, 2025

- EUROPEAN PREMIERE OF ‘PIECE BY PIECE’ STARRING PHARRELL WILLIAMS TO CLOSE THE 68TH BFI LONDON FILM FESTIVAL — August 20, 2024

- INTERVIEW | ILLUSTRATING INCLUSIVITY… A CONVERSATION WITH JOELLE AVELINO ON BRINGING HER BOOK ‘A BOOK FOR PEOPLE LIKE ME’ TO LIFE — August 9, 2024