In 1960, at the age of eighteen, George Jackson was accused of stealing $70 from a gas station in Los Angeles. Though there was evidence of his innocence, his court-appointed lawyer maintained that because Jackson had a record (two previous instances of petty crime), he should plead guilty in exchange for a light sentence in the county jail. He did, and received an indeterminate sentence of one year to life. Jackson spent the next ten years in Soledad Prison, seven and a half of them in solitary confinement. Instead of succumbing to the dehumanization of prison existence, he transformed himself into the leading theoretician of the prison movement and a brilliant writer. Soledad Brother, which contains the letters that he wrote from 1964 to 1970, is his testament.

In his twenty-eighth year, Jackson and two other black inmates — Fleeta Drumgo and John Cluchette — were falsely accused of murdering a white prison guard. The guard was beaten to death on January 16, 1969, a few days after another white guard shot and killed three black inmates by firing from a tower into the courtyard. The accused men were brought in chains and shackles to two secret hearings in Salinas County. A third hearing was about to take place when John Cluchette managed to smuggle a note to his mother: “Help, I’m in trouble.” With the aid of a state senator, his mother contacted a lawyer, and so commenced one of the most extensive legal defenses in U.S. history. According to their attorneys, Jackson, Drumgo, and Clutchette were charged with murder not because there was any substantial evidence of their guilt, but because they had been previously identified as black militants by the prison authorities. If convicted, they would face a mandatory death penalty under the California penal code. Within weeks, the case of the Soledad Brothers emerged as a political cause célèbre for all sorts of people demanding change at a time when every American institution was shaken by Black rebellions in more than one hundred cities and the mass movement against the Vietnam War.

August 7, 1970, just a few days after George Jackson was transferred to San Quentin, the case was catapulted to the forefront of national news when his brother, Jonathan, a seventeen-year-old high school student in Pasadena, staged a raid on the Marin County courthouse with a satchelful of handguns, an assault rifle, and a shotgun hidden under his coat. Educated into a political revolutionary by George, Jonathan invaded the court during a hearing for three black San Quentin inmates, not including his brother, and handed them weapons. As he left with the inmates and five hostages, including the judge, Jonathan demanded that the Soledad Brothers be released within thirty minutes. In the shootout that ensued, Jonathan was gunned down. Of Jonathan, George wrote, “He was free for a while. I guess that’s more than most of us can expect.”

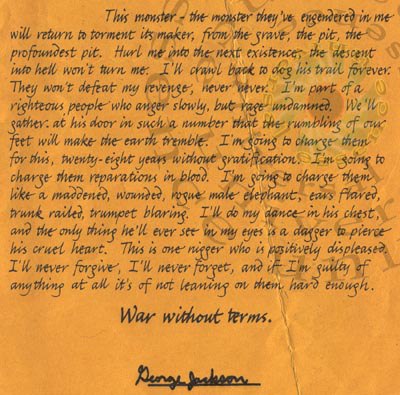

Soledad Brother, which is dedicated to Jonathan Jackson, was released to critical acclaim in France and the United States, with an introduction by the renowned French dramatist Jean Genet, in the fall of 1970. Less than a year later and just two days before the opening of his trial, George Jackson was shot to death by a tower guard inside San Quentin Prison in a purported escape attempt. “No Black person,” wrote James Baldwin, “will ever believe that George Jackson died the way they tell us he did.”

Soledad Brother went on to become a classic of Black literature and political philosophy, selling more than 400,000 copies before it went out of print twenty years ago. Lawrence Hill Books is pleased to reissue this book and to add to it a Foreword by the author’s nephew, Jonathan Jackson, Jr., who is a writer living in California.

Rishma

Latest posts by Rishma (see all)

- INTERVIEW | TRELL SAVONE: FROM BUNKIE TO THE WORLD WITH “SHINE” — June 30, 2025

- NEW MUSIC | MCSOLOMON AND DERAJAH ‘KINGSTON TO LONDON’ — June 30, 2025

- REDMAN RETURNS TO THE UK THIS SUMMER FOR HIS LONG AWAITED TOUR — June 26, 2025