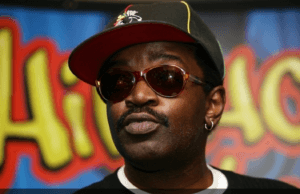

Wild Style is still as iconic as it was 43 years after its debut. I caught up with Fab 5 Freddie before its 4k world première at the BFI London Film Festival.

Wild style captured a movement just as it was being born. When you think back to the very start, what was the spark? I’ve read that it was you that came up with the idea for the film?

I had the basic elements of the film, and then got with Charlie Ahern, and we collaborated. But you know, my motivation initially or my main aspiration was wanting to make paintings and be a visual artist. I also had aspirations to explore other creative areas. In thinking of myself, being a visual artist, being black, I thought, man, it’s going to be incredibly difficult. But I felt like these elements that were going around at the time; the breakin’,the rapping, the DJing and the graffiti, I felt like we could join them together to show people the force of the creative energy coming from inner city youth that were almost always depicted in the media in a very negative light. The rhetoric was always these are young criminals, these young black and Latin people. That really was a problem for me. I felt like if we could show them another side of who we really are, because we’re not just what they tried to make us out to be, it would be a great look. Also, when I come in as a visual artist, people will have a better understanding. So those are the kind of ideas in my head about why I wanted to see this as a film. And as you probably know, I met Charlie at a really big art show in 1980 and I pitched it to him, and he said, Let’s go. Let’s make a movie.

So the initial conversations about the film, like I’ve read in the book Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, by Jeff Chang, were in this abandoned massage parlor in Times Square?

There was a massage parlor in New York City back then. It meant a whorehouse, essentially. Times Square used to be a red light district. It was a component of all the Broadway plays and big movie theaters. You know, sex and prostitution. That was all that went on in Times Square back then. Anyway, this was a former massage parlor aka whorehouse, and it had been turned over to a group of artists that Charlie’s brother was a big part of; they were called Collab, short for collaborative projects. So they threw this humongous art show with all kinds of emerging artists, and it was on the front page of the big kind of cultural alternative newspaper at the time. I saw that, and it’s like, “Oh, my God, this. I want to be a part of this.” And so a friend who was an art curator, took me to one of the first events. They had just opened. The big story was on the front page of the paper that week. It was called The Village Voice. I don’t know if it still exists. Anyway, that’s where I met Charlie. Charlie had made a super low budget underground movie about Kung fu.

Yes, it was called The Deadly Art of Survival.

And when I was connecting with Lee and strategizing on all this stuff, I had seen posters up in his neighborhood, and I knew it was one of those underground films that I wanted to help make. And so at the art show, I saw the poster for this film. I said, yo. And I asked my friend that brought me, Diego Cortez. I said, “Man, who made that film?” He said, “Oh, John’s brother, Charlie, he’s right over there”, and that’s how it all began.

So cool.

I’m so surprised. To be honest with you, some of this stuff is still big and means a lot to people. I’m still kind of blown away by that. We weren’t planning on it lasting like 40 plus, almost 50 years. I mean, in terms of the film and stuff like that.

You’re in the film. How was that like for you to step in front of the camera and essentially perform/act?

First of all, many people think that I’m from the Bronx because most of the people were. I’m from the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, and had no intention whatsoever to be on screen. It was never a part of my plan. Charlie, kind of, you know, convinced me, and I tell the story all the time. I was still living at home in Brooklyn in Bed Stuy, hanging out on the scene in Manhattan. It’s a very long train ride home in the early hours of the morning, at the club and all that kind of stuff. So I thought, when he was pitching it that the few 100 extra dollars a week would allow me to get my first apartment on my own, because Jean, Michel Basquiat, who we were both very close at the time, had recently met and were on a similar track to make things happen, I used to be like man. Jean lives in the city. He was crashing at people’s places, here and there, but it was agony to take that long train and ride home. So anyway, so that’s that. I’m not from the Bronx. I’m from Brooklyn.

I was definitely acting because that wasn’t me. I was not prepared to be on camera, but I looked at it and said ”Okay, I’m gonna have to if I’m gonna do this. I gotta, otherwise what am I gonna do?” So there were a couple of characters. There was one guy who was a legendary graffiti writer who passed away. His name was CASE. When we were researching the movie, we’d met him at one of our outings for research. He just has such a colorful and interesting way about him that I liked immediately. So he was one of the inspirations for the way my character was just so slick and talks and says cool things. So it was something I had to really work on, to put together, because I’m actually kind of low key.

I guess I might be considered hip and cool, but I often think of myself as somewhat nerdy, because I read. I’m curious about everything. But I was able to just adapt this persona, if you will, that, I guess worked somewhat, playing this character thing.The other inspiration for the character was another graffiti writer but a lot of my idea about creating him as a character for the film was theoretical to me. The connection (graffiti, Mcing, breakin’, Djing), I knew about, but we hadn’t found an actual example of somebody who had been really prolific in graffiti and also was in hip hop, and that was a guy, sadly, who’s also passed away not long ago, named PHASE 2, and P.H.A.S.E was the link that I was looking for. In fact, he stopped doing graffiti. He created flyers, adverts, little handouts for one of the early Hip Hop clubs or for the early Hip Hop parties. So my name PHADE was inspired by P.H.A.S.E. And so that’s a long answer to explain.

Later, when I’d gone, they hosted the show on MTV,

I was just about to ask,

Now I’m getting asked to do that, and the fact that I was in the movie, that I knew Blondie and Rapture and all this stuff they were pitching for me to do the show on MTV. This is the guy that can do it. I was like, Well, what am I gonna do? Oh, I’m gonna be, like my Wild Style persona that I created, you know.

I was literally gonna ask, did that help to prepare you to be a global face of Hip Hop?

Of Hip Hop? Yeah, I had to go back. I mean, you know, once again, Wild Style still was a very small underground film, and it still is, in a sense, even though it’s the first and considered a classic cult hit, all that type of good stuff. When Yo! MTV Raps came around, it was really like wow. I’m on TV and cable was still new, so not everybody in the country had cable like they do now. So even most of Manhattan still didn’t have it. Yet they wired up the borough of Manhattan first, and then later, other parts of the city, and so everybody didn’t know what this cable thing was, which people had heard about it, but cable was still this new fascinating thing. And then this channel that played music videos was also a new thing. They weren’t playing much of any black music, which you probably know. And so that was problematic. And then they decided to say, well, let’s give this rap thing a try, and let’s get this guy to host it. The ratings went through the roof. So that was how that all went. But with Wild Style, yeah, it was still like an underground project that would go to different cities. I mean, one of the great things is that I’ve just written a memoir coming out in March. It’s called Everybody’s Fly, and that’s where I get deep into these stories.

There’s this special story for me, particularly about England, when Wild Style came out. There was a première party at the ICA, which was on The Mall, which I didn’t know anything about The Mall or whatever. They hired these young black guys to be the DJs for me and I became really cool with these guys. They had a sound system. They were called Mastermind Roadshow. These guys were early pioneers on the scene in London. They were playing at outlaw parties, and were introducing people to a lot of this music. They were later some of the guys that became a big part of Max and Dave, which if I’m not mistaken, became a big part of pirate radio, which became big. But anyway, these guys were the DJs that played at the opening party, and I’ll never forget how excited they were, because they couldn’t believe that this was happening. We’re gonna do this party at The Mall. I didn’t understand the significance. Like, this is essentially a part of Buckingham Palace. Or what that meant. We tore that shit up and had a lot of fun. I got on the mic. They had all the right records to play, you know what I mean? I turned them on to a couple of things. And yeah, I learned a lot about the London scene at that time through those guys, and went to a few of the outlaw parties that were going on at that time. I got into that because those guys whose parents, I later would understand, were part of the Windrush generation and how significant it was for them to be able to connect with American culture and to be connected with Jamaican culture to help get their own identity, their own flavor together. So anyway, that was all a big learning thing for me.

Did you ever imagine it would be screened globally?

Everything had completely changed in terms of our initial plans or thoughts because of how the film business and everything works, everything has been turned upside down, inside out, because of digital and all this stuff. But at that time Charlie being plugged into the independent underground, I mean, literally underground film scene, there was a way where you would hopefully get the film screened, maybe get it put up or get it featured in some film festivals, to try to reach as broad an audience, but our main intention was Hip Hop.

It wasn’t even called Hip Hop yet, but that community in New York City, the kids that were part of this culture, that knew what was going on, and the downtown creative art scene that we were both connected to, that was our target audience. Because for most filmmakers making films like that was the thing they wanted; their friends and the people in the art community, people that were also making underground independent movies for very low to super low budgets. That was the audience. But then Hip Hop as a form on record hadn’t really broken out. Rappers Delight had come out. But still, if you heard it and gave two thoughts, most people thought this was some fad type of thing going on. It was a fun record, Sugar Hill Gang’s, Rappers Delight. But most people didn’t think much of it, because it was good fortune. In fact it is important to note that we wouldn’t have even got the movie made the way we did, because we went to all these independent sources for financing for independent filmmakers. None of them took us and gave us a deal in America. Or New York, where we met. But people from the fourth channel, which had recently started, liked it and they invested. They bought the rights to show it on tv. And the second channel, channel two in Germany, ZDF, did the same thing.

So with that money that we got from the fourth channel and from ZDF, we went back to other people and said, “Look, we have a decent amount of money here”. And they were like, Whoa. That convinced some people to then get involved. So that got the ball rolling, which for me, with my background was monumental. Max Roach, a really important drummer from the jazz scene, was my godfather and a close friend of my dad. I remember growing up with the stories of how difficult it was, and how it was a lot better when these guys traveled to Europe. It wasn’t the aggressive, back of the bus type of racism that America had in that time. And I remember the way they would just hear Max and my dad talk about how these musicians were treated so much better. People just didn’t take it. They didn’t have all the racist baggage that they would consider. You know that has gone on in America. It still goes on. So those opportunities were super exciting that the film was going to be released in Germany, in England, and stuff like that.

So it was quite surprising and continues to be surprising how the film is embraced overseas. We figured, well, England, they speak English and our rap being in the English language and words, the English will get it, but the French, the Dutch, the Germans and all these other people, that was mind blowing. We had no idea that it was going to translate because, you figure these people ain’t going to understand what’s being said, but they picked up on the energy, the vibe, that raw, street, something that we showcased. They all said, Yes, we got it. And now here’s our version. We got stories to tell as well.

When you watch Wild Style now, it’s a time capsule of New York City back then. What do you remember most vividly about the era that no longer exists today?

How about everything! Things change. You know, that’s a natural process. New York has changed so dramatically. I guess, if you’re benefiting from the changes; You own property and can make money off your real estate and high rents and get big money. But on the other side of it, it’s like, none. Sometimes, okay, so I live in Harlem, and sometimes I’ve had to go to the Bronx, which is just right over the bridge from Harlem, which is in upper Manhattan. I’m driving around looking for things. There’s a lot of car mechanic places to get your car fixed in the Bronx.

So sometimes I’m up there and I’m kind of lost, but I’m trying to get to this area, in that area, and then it hits me, oh my goodness, like, you’ll be on a block, and there’ll be a nice block, a couple of blocks of nice, two story family houses that were probably built sometime in the last 20 or 25 or so years. It’ll hit me that, oh my god, this is one of those blocks where other buildings look like they’ve been bombed out, like Gaza, as sad as that is, or Ukraine, like that’s how horrible it used to look. And then I realized this is one of those many blocks and buildings that have been rebuilt, and then it’ll hit me how dramatically different and oppressive it used to be. So that sometimes hits me. And then I’ll just go into a zone where I remember how edgy it used to be in the Bronx, back then and other parts of New York City as well. Things are just so different. Like, I mean, the same thing going on in England. I’ve seen gentrification over there in areas like Brixton. When I was connected with Mastermind Roadshow, I would go and stay in those guys’ homes. They reminded me so much of being in Brooklyn, like, black Brooklyn back then, you know? The Jamaican food, the Caribbean vibe. It was like déjà vu, like, Am I back in Brooklyn?

Yeah, I’m currently living in Brixton.

Yeah, I know it’s still got flavour, a little.

Just holding on.

Well, that’s, unfortunately, a lot of what’s happened in New York City, in many areas. I tell people, Look, I’m gonna keep it a buck with you. White people have been lied to, and they were scared. It was never as bad as they made it out to be. But that’s how it was in New York and now in Harlem, where I live, you know, it’s, it’s very diverse now, as well as in the Brooklyn where I’m from, the same thing, homies that grew up with me and my era, we still talk about how we still can’t believe how much has changed, sometimes it’s it’s a good thing, and sometimes it ain’t.

When you witness Hip Hop now, the sound, imagery, the business model of it all. What parts make you proud and what parts make you nostalgic of the early days?

Well, I’m pretty open to music changes, every era, every generation. You’re going to have that stuff that you grow up with, that you love, and then something new is going to come around. And a lot of times people, when they grow older, they’re not with that, that newer thing. So I’m very conscious of that, so I’m not overtly, extremely critical, but there is a lot of nonsense to some of the younger rappers. I mean, rappers in every era have done nonsense, if you will. But I think the thing that’s somewhat really the major difference, besides the changes in the music, is that way we get access to the music; the streaming, the YouTube, I mean. All of this technology, which is great because I’ve always been up on it and a bit ahead of the curb. But it’s unfortunate, some of the aspects of the way the business was structured.

If I like a record, I want to read all the information on the back of what used to be the album, then the CD. Now there’s nothing. Like, where do I find out? If I want to know, who recorded this, who was the engineer? There’s so much stuff that you don’t get access to, and that’s problematic. And in America, maybe the same thing in the UK, new records were released on a Tuesday. That used to be the day when new music came out. So in a certain week, you’d be like, Yo, so and so just dropped. You’d be like, Oh, my God, is it yo? Is it bank? Oh, you see. Now it’s so all over the place. Everything is so scattered. So there’s good and bad that I see in it, because you can get access to so much of everything.

I’m in Lisbon right now. I was just in Nairobi, Kenya for a couple of weeks. And, you know what’s amazing? I did some podcast interviews over there. They totally know my whole story because it’s all accessible. It was a lot more work to get this information before but it’s also good that you have maybe easier ways to find information now. I’m that person that reads everything and has books and stuff like that. I’m constantly looking at both sides of the coin, but once again, when I was in Kenya, I asked about some stuff. I can go right on Spotify. Can go right on this. I can go to YouTube, and I can see more examples of it, and I can hear it immediately, and they can do the same for stuff coming out. I’m just happy to see people do their own thing and be original with it. You know, there was a time, well, when I first was over, back in that period, there were guys trying to rap, and they were all in, you know, trying to emulate what was coming out of America, New York, whatever. Then when I was doing Yo! MTV Raps, I went over and I interviewed London Posse. They were a big deal back then, but I knew then these guys were following what was going on in America. And then they came with that whole style that was totally theirs, the whole Grime thing. Dizzie Rascal dropped, and then I’m like, Whoa. Now this is what I’m what they needed, their own thing, and now you got super, mega artists. Those cats that have emerged. That’s what I like to see: when other cultures, other places, figure out a way to make it theirs. I mean, so there’s many different styles. Drill started in England, if I’m not mistaken? Drill came over and that’s some of the most dangerous stuff when you hear what Chicago drill did to those guys. It is beyond sad, the way they literally doing the things that they rap about.

A lot of rappers would talk about doing gangster stuff, but not really do it in Chicago and other places where that got popular. I mean, it was unfortunate, and it’s because of the system. You could shoot a video on your iPhone, and we put it all out on YouTube. It has an incredible amount of influence, and young kids that are not that educated, don’t have good family structures, are just doing horrific things, and that’s one of the saddest things. You know, it’s always been some edgy drama going on in the hood, but some of that stuff is just beyond the beyond for me. So that’s problematic.

When you were making Wild Style, what did you hope people would take from it and looking back at the world now, do you feel like your original vision has come to pass, or has it evolved into something completely different?

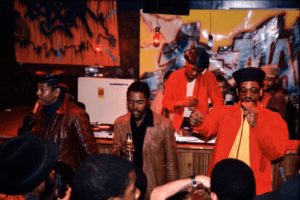

Yeah, I think a part of filmmaking, and other filmmakers could attest to this, is things you envision, things that come out, you hope will come out good, but things change and evolve. It’s an organic process of filmmaking, but being that I was the one that really had a sense of what Charlie learned really fast, I was super impressed with introducing him to this thing that was then completely underground. Introducing him to the hardest core aspects of it. And Charlie was liking all the stuff that was really good. And I’m telling you at that time, in context, it was so different and so rare. Nothing sounded like that when you got with the right DJs cutting up those extremely obscure break beats. They were creating a mood and sounds that weren’t happening anywhere else. And Charlie got it right away. So our efforts were to capture that real and that raw, and when he was then able to understand what I introduced to him, we got to show the world what the real and the raw really was. And so the fact that we were able to do a decent job, and the first screenings in New York City, where the real heads in the film came from, guys from the hood came and went crazy.

It was the most incredible satisfaction. People literally screaming out, “yo, there’s so and so. Here’s my train going by. Yo, that’s my homie over there. That’s so and so there,” laughing at everything when Busy Bee is on the mic, telling the people at the party, everybody say, “hold up” and the whole audience doing in the theater. Moments like that were like, oh my god, we did it. And that was satisfying. But the fact that it traveled so well around the world was really a mind blowing experience, because we never really anticipated, like kids in all these other places we’re going, to connect and get in sync with that energy.

Finally, what do you want young artists and filmmakers today to take away from Wild Style?

My parents were the last people in Brooklyn (I used to think), to get color tv. My father wasn’t a big tv guy. Two films that we liked and were big inspirations were The Harder They Come, and Black Orpheus. So those films introduced the world to new forms of music and a whole new energy around the people. And that was something in our minds. We feel like we captured that. That was a driving thing, to be as real and raw as those films were, which had real people in the films as well, The Harder They Come, these guys were the real dudes in Jamaica that introduced the world to Jamaican Rasta, Rude Boy, that whole shit. Black Orpheus did that for Bossa Nova, and you got to see how black it really is in Brazil. Beautifully photographed and just exciting. We wanted to do that with our film, and I feel we got kind of close to that. And so those were the inspirations. I just hope people, if they see it, they see it. They could get an understanding of where it came from. It was a very humble beginnings. That is another thing I like to point out.

A lot of artists these days are chasing the proverbial bag. There’s nothing wrong with that. But in the beginning, people were motivated by trying to be original, trying to have a style that stood up against anything. I think a lot of times, some of the younger acts that I hear coming out of America, things sound very similar. I know music changes, but it was very important to be distinctly different, and the great artists always are. So I know artists want to do it for various reasons, but if you really want to stand out and last the test of time, you have to be original. You can’t sound like nobody else. You’ve got to figure out that thing that nobody else has. And if you can figure that out, you’ve got a shot to really stand as a real creative person, making film, making music, making whatever you do. You feel me. Just be original. That’s what I’m about. I think that’s a good thing.

You’ve put a fire under my ass about my own art. So thank you. Your book Everybody’s Fly is due to come out in March 2026?

Yes, March, Everybody’s Fly. Everybody’s flying. I go deep into a lot of this stuff. Wild Style is a big part of it, and making art, and, you know, hooking up with all the incredible people on the New York art scene, and all the blessings that I’ve had. The great people, many of so are not here anymore, but made an indelible mark. You know, Jean Michel, Keith Haring. A lot of people, a lot of heads that were all in this shit together. There was a whole crew, trying to make moves.

Thank you so so much for your time, for your energy, for your amazing words.

Valerie Ebuwa

Latest posts by Valerie Ebuwa (see all)

- INTERVIEW | CHARLIE AHEARN ON THE MAKING AND MAGIC OF WILD STYLE — October 20, 2025

- INTERVIEW | 43 YEARS OF WILD STYLE: FAB 5 FREDDY ON LEGACY, ART, AND STAYING ORIGINAL — October 14, 2025

- REVIEW | THE POWER (OF) THE FRAGILE : A MOVING DANCE PERFORMANCE EXPLORING FRAGILITY, DREAMS, AND BOUNDARIES — July 5, 2023