Can you give me an idea about CAGE and the kind of work you do?

Can you give me an idea about CAGE and the kind of work you do?

(Asim) I started my masters in October 2003 and on the first day of enrolment; I knew what I wanted to do my dissertation on which was Guantanamo. It’s a thing that changed my world view. I was gonna go into corporate law and I changed all my subject to human rights and international law because of these orange jumpsuits. I was doing my research and a link for CAGE Prisoners came up and I thought these guys are thinking about it from a Muslim/Islamic perspective, what does it mean to have pow’s in Islam. I emailed them and became a volunteer. I helped by uploading pdf’s and journal articles or different things that I can access because of my university account. When I finished my masters, I went to the founders and said let’s turn this into and NGO. Initially we were focused on research and reports. It was about analysing secondary source data and shifting patterns. At that time mostly speaking to families. Within a year people like Moassam Begg had been released and so we had data coming from Guantanamo from this early group of released individuals. In 2005 we did our first report which was about the dessication of Qur’an inside Guantanamo, which had all this primary source material.

What kind of things were happening?

(Asim) They were flushing the Qur’an down the toilet, stamping on it, using it to coerce the detainees. We were the first people to publically talk about it. The key contributions in that first year were, because our team was able to read Arabic, Urdu and English, we were able to access lots of different sources in relation to the names of people who were being sent to Guantanamo, something that a lot of western outlets and NGO’s weren’t able to do. They ended up taking our list of detainees and making it their own. The Washington Post actually cited their own list to us. We knew the list wasn’t perfect but at that time it was the most definitive list out there. The major role that we played was telling human stories about who these people actually are and maybe providing an alternative narrative. Early on I would make field trips to Pakistan and meet with families and talk to them about their family member. We heard stories about local rivalries with other families being used as a way of selling these people to the Americans because they were paying five thousand dollars a head. This then became an easy way to get rid of certain patriarchal structures that existed within that society. Two thirds of those in Guantanamo weren’t even picked up in Afghanistan; they were picked up in Pakistan; not even in the battlefield, which is often forgotten.

Initially we were really focused no Guantanamo and secret detention. Then we increased our remit to anything that related to the war on terror, campaigning about individuals held here. After 7/7 Prevent came in our focus shifted in order to expand our remit.

What kind of challenges you face when doing what you do?

(Dr. Layla) Even something as simple as setting up an event, venues end up cancelling on us because they’ve been intimidated or coached by prevent or even police officers, telling them that they’re hosting extremists. There’s that kind of intimidation.

(Asim) Last year I wrote an academic paper for a journal based on a model by a cultural theorist who studied the black civil rights movement, in particular the Black Panther party were politically repressed in America. He built a model on state repression and what the different tactics on state repression are in relation to civil rights movements. I analysed our history and engagement with the states based on his model. I found that cage has been through every single aspect of the state’s repression except one; none of our members have been killed by the state yet.

When they shot Jean Charles de Menezez in the back of the head, they thought they were shooting a Muslim. People forget that. They had an assumption built in based on his look; they thought he was a guy named Hamza and they shot him twelve times in the back of the head because they thought they were shooting a Muslim. That’s Islamophobia even if the victim isn’t Muslim. In a Black Lives Matter world, where the police have been known to extra-judicially kill people on the streets of London, it’s not outside of the realm of possibility.

We have our bank accounts closed, we have our events shut down. There’s media campaigns against us and roll out politicians to speak against us. Every single action mode of repression, which is what he calls it, we’ve been subject to.

They don’t see structural racism. They don’t believe and they don’t understand how judges, lawyers, prosecutors, police officers, jury members can be bigoted and racist because that would mean admitting that society is even more messed up than it already is. For your bog-standard liberal, they wanna believe that actually most people are just decent people, and they’re willing to do decent things and yeah, that’s true to a large extent, but if you remove race and racism from the equation that you’ll never understand how certain communities are so systematically disenfranchised. And that’s why it’s so important that we connect what’s happening in certain movements, like what’s happening to black people in America with what’s happening here.

Again, as I write about in the book, the fact that George Zimmerman based his assumption about killing Trayvon Martin on a PowerPoint presentation that he was given about the signs of dangerous people to look out for; I mean the reality is that they were basically describing black people. So he was already prepped to find these threats; and so when Prevent does exactly the same thing where it says here are all the things to look out for, and in an environment where the media is constantly Islamophobic, you are primed to find Muslims as potential suspects. That’s how structural racism works, it requires everyone to get involved. So when we talk about what challenges we face, there’s ones we face specifically as an organisation but those challenges are within an environment of structural racism where your average person doesn’t understand that they don’t live in the same world that we do; they don’t live in the same world that black people do. These are different worlds that we inhabit, and because we inhabit different worlds, our starting point in relation to our relationship, not only to the state but to state institutions, is completely different.

What are some of the objectives of CAGE?

(Dr. Layla) I think it comes back down to the strap-line; Witness. Empower. Justice. Witness; to actually provide some sort of documentation for the future, we’re hoping that this will become a part of history and people will look back and realise. To empower the community because it doesn’t help when people are going through some of these things, but aren’t able to speak up or are shunned by their own community. And to seek justice; there are avenues they can pursue to gain justice.

(Asim) This is about principles. Some of our clients aren’t particularly nice people; they can be people I spent time arguing with because I don’t agree with their belief system. The idea of Justice is to take the most despised person in society and ask “what do rights look like for this person?” and the problem with the Muslim community is that we think very short term so “we don’t like x, and we’re willing for the law to come in and deal with that person so we can separate ourselves.” But once the law is entrenched, the person is gone, but the law is still there and it can be used against other communities. Nobody thought the extraction act would be used against bankers. It’s much harder to repeal a piece of legislation than to stop it from becoming law in the first place. But once it’s law; everyone just plays their part and follows the law.

(With Prevent) When we’re talking about people having their kids removed, you’re average social worker knows this goes against the ethics of their profession. So you see this cognitive dissonance emerge where they know something is unethical but they are required by law to do something they wouldn’t otherwise do. That’s part of what we campaign against; it’s about the principle, not just we want innocent people to get off; we want a better society a more just society and that idea’s transcendental. It’s not about bringing in Islamic law system, we want British society to be the most ethical and just society that it can be. It’s not about government it’s about governance.

What can we as a Muslim society do? And where are we going wrong?

(Dr. Layla) I think Fear is a powerful tool. I think it’s difficult when you’re the suspect community. One thing that CAGE has done well is to see things at the very early stages and warn against it. In 2015, Asim said “I read this (Prevent) as children will be able to be removed from their families.” and there was several quotes of people saying we scaremongering etc. and a few years down the line today we’re launching a report with evidence of that happening. I think sometimes seeing and being able to come out of the bubble and having long-term thinking as a community.

(Asim) I completely agree. A lot of muslims just want to get on with their lives and just be a part of society, problem is part of what society? If you have a narrow perception of what it is to be included in society then your version of inclusion means being a neo-liberal capitalist who does everything in a halal way, so your food becomes halal and your clothing, holidays and events. If that means having made it then you have a narrow perception of society.

It’s about being aware of where we are at any given moment, and our communities often have a very narrow perspective of what inclusion means. So they say if we apologise for terrorism and condemn it, then they’ll just leave us alone. But in the saying of that they fundamentally shifted their own place within society as being outsiders. You’re humanity is derived simply from your existence and presence; it’s not something you get invited into.

I don’t think the community is spiritually and intellectually able to deal with the challenge of the war on terror because of the fear that it brings.

I noticed how many different cultural references you used in the book as well as Muslim perspective.

(Asim) My entire early political upbringing was very much rooted in hiphop, whether it was NWA, Tupac, Wu Tang Clan, the whole of the west coast rap genre was something that was very important to me.

For me, knowledge is knowledge. There’s good knowledge and bad knowledge, but anything for me that makes a contribution is something I can take from. I’m not gonna reject something Tupac is saying just because it’s Tupac saying it, I gonna ask “what does this mean to me in my life?” is there something I can take away?

Hip hop was very present in my understanding of race. With hiphop we understood the position of race and gives us an idea of how we can assert ourselves in a way that’s meaningful. It’s quite upsetting at times to see Muslims not giving black culture it’s due in terms of what it gave to a generation of young Muslims such as myself who weren’t politically conscious and who needed something to help them understand the world in a way that made sense; like Tupac’s song “Brenda’s Baby”, which many young people were moved by.

They say police officers are being killed because of NWA and Ice T and Tupac. Their argument is black people are killing police officers because of this music. But white people listen to the music aswell, why aren’t white people who listen to this music killing police officers too?

Certain types of white people who are caged in racism may see it as a natural part of the barbarism of people of colour because of their ideas around eugenics and phrenology and so on. We’re saying no… the reason why people have higher levels of anxiety inter-generationally in relation to their relationship to the state etc is because of this transmission of trauma throughout these generations, which are all based on environmental factors based on slavery, colonialism, police brutality and socio-economic factors which are all environmental factors which lead us to this place where we have this antagonism.

For me the most fascinating group in relation to this trauma that we currently face with the war on terror is the group that weren’t politically conscious when 9⁄11 took place, maybe they were nine or ten years old when 9⁄11 happened. They weren’t able to discern what the world was before then, so when they start becoming aware of what’s going on in media rhetoric and being constantly subject to these narratives about how problematic Muslims are or how problematic people of colour are; they don’t have another period to reflect that against, for them Muslims have always been a problem since they’ve been aware. I can remember the 80’s and being chased around by skin-heads and nazi’s and getting into fights with them. I also remember the 90’s and racism hadn’t ended but it had become impolite to be racist in society, it became very out of vogue to be publically racist.

Then 9⁄11 happens and the war on terror comes in and it’s like open season on Muslims. For me, I can see the different shifts and patterns and I understand that there are certain elements that are race based, certain elements to do with secularism, elements to do with Islam both happening within Islam and from the outside against Islam. But for a young Muslim growing up in this environment, they only know that they have been securitised from day one of their consciousness. That’s the group I worry about most; I don’t worry about my generation because we knew something different. Even in terms of our ideas around jihad; we saw Bosnia, Kosovo, Chechnya, we saw Afghanistan; we had a reference point for what virtuous jihad looks like even within a modern context. As opposed to young people who only see it caged in terms of ISIS and Al-Qaeda. When we were young the media we telling us about Mujahedeen, it wasn’t talking to us about jihadists. Even in Bosnia they publically used the word Mujahedeen in the media.

Do you feel like there is a collective-trauma that needs to be addressed and dealt with?

(Asim) Without a doubt. All of our communities suffer from this collective trauma because we all configure ourselves in relation to the war on terror now, even in our own private lives. Even in our joking with one another we internalise the narrative of the war on terror about who we are or who we should be. We’re constantly navigating around a box that relates to the war on terror and the state’s view on who we are and how we should be. The way we use language is extremely important.

We construct Islamaphobia ourselves, we construct our own internalised trauma about the war on terror, but it’s in direct relationship to how it’s externally constructed for us. We see the dominant framing and we adopt that framing because we can’t do anything about it and work within it’s parameters in order to change the world except that’s not changing the world, that’s trying to squeeze into it; to find a space where you are not seen as a threat within a dominant discourse of how you should be.

What does it mean to be part of the Ummah, to be part of a community that’s striving for justice in the world that we live in today? Is it possible for us to talk about a just society in the UK by just pushing for an end to Islamophobia? I don’t think so, that’s a very narrow view of what’s important.

Had Muslims been smart enough to understand this before they would’ve put all their effort in dealing with racism and not even thought about Islamophobia. Pre 9⁄11 they would’ve just said racism exists, we all need to tackle racism in our society. Racism is the platform on which every other form of institutional racism then exists. So if you didn’t understand that black people in particular were being discriminated against, then what you did was allow for a platform to exist on which the building blocks of Islamophobia are formed. The two can’t be separated from one another. If we say let’s end Islamophobia, but then will that end racism too? The two are inextricably linked to one another.

What is the conversation around bringing all forms of oppression under the same banner?

(Asim) One of the things I was very aware of was that I was writing it as a man. The book went through multiple rounds of scrutiny by Islamic scholars from different traditions, political activists from different traditions, because I need to know if for all of our traditions this is something that has some worth as an introduction to this type of politics. So part of that process was giving it to lots of very smart Muslim women who either academics on race, or academics on Islam from various traditions. I say to them “if you read this as a woman, do you feel that it still speaks to you in a way that’s true, or do you feel it undermines you in some way that I have a blind spot towards?” There were some changes that I made in terms of how Muslim women are sometimes otherised, how they’re not brought into the debates and discussions we have. But for the most part they all said the same thing which is they felt that it spoke to them as well.

I did an interfaith discussion about my book and it was incredible to have a group of Jews and Christians; everybody in the room already took God as a given so that was nice to be in that space. For them to reflect on the book from their own traditions; they were surprised to see so much written about the Holocaust for example. So even with MLK, who is a great political figure, but people often forget about the religious aspects of the arguments he would make, and those were fascinating for me. MLK is making religious arguments for me in the book, not just political ones.

Is there a conversation around stopping history from repeating itself?

(Asim) That’s part of the book; to present history as being cyclical. Akala says “Time is a cycle, not a line.” That’s exactly what I’m trying to present, but what I do is I present it as modes of action so that’s why I use this term “modalities of oppression” because it’s the same mode of oppression again and again. Don’t look at the person, look at the action that they’re taking; people concentrate too much on what the person looks like. You’re looking at the superficial aspect of it, look at the policy. What does the policy look like? If the policy looks repressive then more than likely it’s gonna go down the same lizard hole. And you don’t wanna follow them down that lizard hole, you wanna cut it off straight away and say “No, we’ve seen this before, we recognize what it is and we’re not gonna fall for that trick.” But you have to understand that oppression follows in cycles and if you don’t get that, you will never see the world for what it is because you’re too focused on the superficial and that will always distract you from what lies underneath; the system.

You only have to read “The Open Veins of Latin America” by Eduardo Galeano to see how you move over history from one period of pure colonisation and the rape of a society in terms of its economics and actually even physically, through to the invention of the IMF and how that systematically destroys societies and communities but you don’t have any critique of that because for you it’s just like well, this is the world we live in. There’s no taking on one form of oppression without taking on another form, and we know the economic system of the world is oppressive; it oppresses people every single day.

Once you accept that the world is a bad place and you have responsibilities to the world that you live in then that just brings all sorts of drama and trauma in your life that you really don’t want to engage in.

On what levels do you think we as a Muslim community are experiencing trauma right now?

(Asim) For me, I think trauma is endemic to everything that’s going on; I don’t think we can escape it. I think it’s something that we should be thinking about more regularly but we don’t because of the way the war on terror constricts us and constructs us both. It’s hard to gauge because there’s not been any empirical studies, even then it’s not easy to measure. These things are usually found out a long time after they’ve happened, but I’ll give you one example, my colleague Mohammad Rabbani was charged by the police for refusing to hand over his passwords. What was interesting was that when we got back to the office, we had literally hundreds of people calling the office line or emailing the office to say we’ve been through that process at the airport and what was interesting was the language that they used; they said it felt like a violation. I felt like my personal life had been violated in some way. All of the language they were using of abuse, of trauma of violation all reminded me of all of the works I’ve ever read of sexual violence. It was so fascinating for me.

I quote Judith Herman’s book “Trauma & Recovery”; what she does really amazingly well in her book is that she charts how the logic of sexual violence is no different than that of political violence, of torture, of coercion, this is all about control. It’s a fascinating book and it reminded me; what is it about Muslims and our trauma with the war on terror? It’s about the fact that we’re constantly being controlled, that we’re constantly being constructed, and therefore of course we feel trauma in relation to it because it’s always an act of coercion in this relationship to the media, in relationship to the state, in relationship to the establishment. There’s always this coercive element where you have to self-regulate your life in order to meet an expectation of how you should be. I’m hoping someone does an actual study into it and actually looks into the psychology of these things because I think there is a degree of violation that the war on terror brings that is deeply problematic.

Young women have all sorts of layers of trauma that they have to deal with beyond just simply being problematized as being Muslim, as women, as women of colour; there are just layers that they have to think about and deal with on a daily basis. A Muslim woman in hijaab is a very visible target in a way that a Muslim man with a beard just isn’t; we’re hipsters now, even if we walk around with rolled up trousers we’re cool. But for women there’s no hiding, there’s no hiding in a hijaab. You are outing yourself publically as a Muslim when you do that.

Regarding Jesse Williams BET speech which you quote in the book, with him talking about the hereafter being a hustle, what do you think is the idea around that as a Muslim?

(Asim) I listened to that speech on repeat just because of how perfectly it captures so much in such a short space of time. It was just brilliant.

The first time I heard him say the hereafter is a hustle, your instinct as a person of religion is to say hold on a second, but then I was like no, I need to listen to this again; I need to understand what he’s saying. For me, he wasn’t saying that the hereafter doesn’t exist, what he’s saying is the selling of the hereafter is a hustle. We will sell you the hereafter, forget about this world that exists. Now I believe this world isn’t a real world, I believe this world is transient, but I also believe that everything I do in this world impacts on my after-life.

So you talk about the hereafter being a hustle, I agree with him that it’s sold as a hustle to pacify us, whereas actually the hereafter should be something that’s sold as a promise if we live in the real world and fight for justice in this world. So that’s why when I thought hard about what he was saying, I really came to appreciate it. I knew it might cause some controversy with people who are a bit unthinking by quoting that. I’m with him one hundred percent, that when our imams tell us that be patient, wait for the hereafter, I agree; be patient but act with patience. That’s the difference; no one is saying be passive with patience; act with patience. There’s no example in the Qur’an that I could find anywhere where Allah says stay in your home and wait out the oppression until the oppression has ended. There is not a single story in the whole of the Qur’an that gives that view, that simply just ignore this thing exists.

So what do you think is the next step?

(Asim) That’s a difficult one for me because as I write in the book; the book didn’t start off as a book, it was thoughts to myself that I was writing as I was in a sabbatical year from my work at CAGE. It was more of a conversation to myself, maybe to my children, to think about where we were right now. For me, before we can talk about solutions we need to get our ethics right. Like how can we talk about the solution if even from an ethical perspective, we haven’t understood where we stand with the state against oppression, against injustice. That core belief system hasn’t emerged yet, so that for me needs changing first.

For me, it’s like an education process that this is like a conversation starter. I want people to criticize the book; I want it to be part of the conversation. That for me is more important than us coming away and saying this is how we’re gonna achieve utopia. I don’t believe in utopia but I do believe in fighting for justice because ultimately justice is with God. I believe that everything will be squared in the after-life. What I want is for people to engage with the book, think about what their place is in relation to the book.

Aisha

Latest posts by Aisha (see all)

- INTERVIEW | 47SOUL INTRODUCE US TO THE SOUNDS OF ELECTRO ARABIC DABKE — October 18, 2019

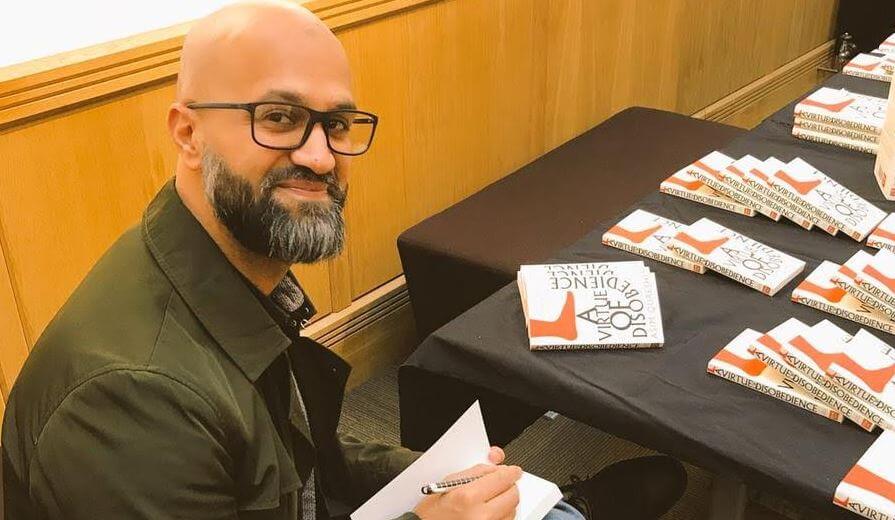

- INTERVIEW | ASIM QURESHI — AUTHOR OF “A VIRTUE OF DISOBEDIENCE” & DR. LAYLA HADJ – MANAGING DIRECTOR OF CAGE — February 19, 2019

- REVIEW | “A VIRTUE OF DISOBEDIENCE”: MUSLIMS IN TODAY’S SOCIETY — February 19, 2019