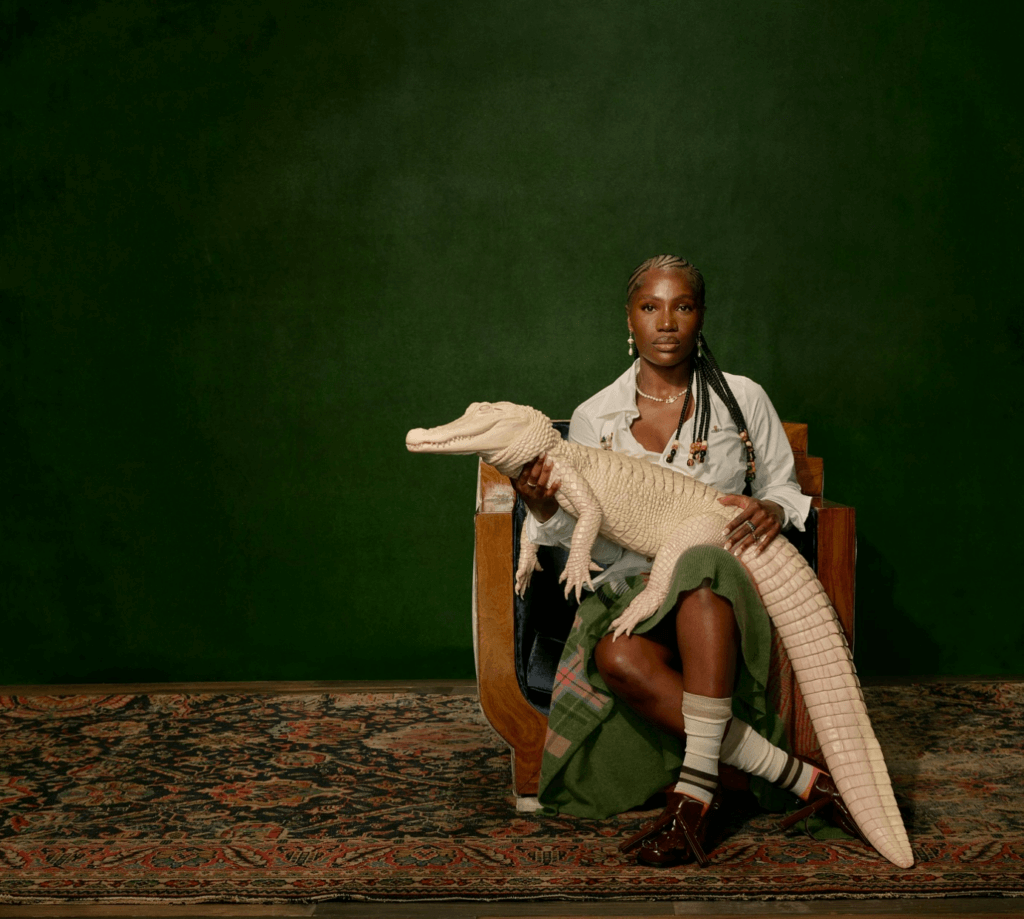

Photography: @johnjay.img

She’s not riding the algorithm. She’s bending it into performance art.

If you listen closely to Doechii, you can hear the future. Not just of hip hop, though she’s bending that genre like it’s origami. Not just of pop, though she’s charting and streaming with a smug wink that suggests she could give a TED Talk on virality if she weren’t busy reinventing it. No, the future Doechii brings with her is more unsettling, and more thrilling. It’s a version of the music industry where intelligence, spectacle, and rage all co-exist without asking permission.

Let’s start with the obvious: she’s immensely talented. But that’s boring. Everyone’s talented these days, the algorithm demands it, chews it up, and burps out another Gen Z darling every six hours. What Doechii has, and what her peers often don’t, is vision. And not in the vague “I have a message” sense. This is the kind of vision that turns virality into critique, performance into protest, and a TikTok trend into a Trojan horse for actual meaning.

Take her breakout single “Yucky Blucky Fruitcake.” It begins with a monologue so charmingly erratic it could’ve been ghostwritten by Issa Rae, and then plunges into bars so sharp they should come with a legal warning.

“I’m a down South, black girl, wanna get rich / I ain’t no dumb bitch.”

It’s a line that sounds like a flex, and it is, but it’s also a manifesto. A thesis. A political act in 808s and eyeliner.

This is a woman who raps like she’s been reading both Bell Hooks and Baudrillard between takes. Her wordplay is whip-smart, her cadence shapeshifts like Missy Elliott doing method acting, and her visuals are a fever dream filtered through postmodern satire. One moment she’s riding a beat like a villainess at fashion week; the next she’s delivering coded commentary on respectability politics while voguing in a gas station.

And yet, she’s gone mainstream. She’s on SZA’s label. She’s performed on Fallon. She’s got the TikTok kids lip-syncing her most viral hooks in Crocs and LED lighting. And guess what? Her message hasn’t diluted one bit.

Because this is the magic trick: Doechii is one of the rare artists who has figured out how to play the game without letting the game play her. She’s studied the mechanics of the algorithm and turned them into choreography. She knows what goes viral, and she weaponises it. Her hooks are sticky, yes, but they’re often smuggling in questions about gender, race, selfhood, and survival under late-stage capitalism.

You’re singing along before you realise you’ve just rapped about being a Black woman in America’s culture machine.

“They call me devil and angel, the same bitch / They want me quiet but still entertainin’.”

That’s not just a bar — it’s the paradox of Black femininity in pop culture, compressed into two lines and delivered with a grin.

And recently, something happened that felt like fate adjusting its crown: Doechii shared the stage with none other than Ms. Lauryn Hill. In a landscape where co-signs come faster than influencer PR drops, this was not just another collaboration. It was canon-building. Because if Lauryn Hill, hip hop’s high priestess of introspection, rebellion, and grace, thinks you’re worthy of her mic, that’s not hype. That’s heritage. It’s not a passing of the torch exactly (Ms. Hill never relinquished it) — but it’s an unmistakable nod: You’re doing it right.

While other artists find themselves neutered by virality — their artistry flattened into brand-friendly “aesthetics” — Doechii somehow expands within it. She uses TikTok like Warhol used the screenprint: as a lens, a critique, a joke you’re not quite in on.

She’s also deeply theatrical. Her BET performance, the one where she goes from full spiritual possession to twerking on a gospel choir, wasn’t just a performance. It was a sermon. It was the closest hip hop’s come in recent memory to true art-pop. Not the safe, Spotify-core variety. The weird, unsettling kind that says, “What if I made you uncomfortable while still making you dance?”

What makes her important, though, isn’t just her aesthetic. It’s that she reminds us that hip hop can still be a site of subversion. That even in an age where so much art is flattened into streaming metrics, an artist strange and specific and unapologetically Black and female can still punch through.

She’s not asking for attention. She’s dragging your gaze to her and refusing to blink. She’s not tweaking her message for the market. She’s redefining the market with every drop, every look, every breathless verse. And in a culture that rewards sameness and punishes audacity, that makes her not just exciting, it makes her essential.

So no, her mainstream success hasn’t diminished her messaging. It’s amplified it. Doechii isn’t selling out. She’s staging a hostile takeover — in full glitter and chaos.

And we should all be watching.

Finally, if you’ve ever doubted Doechii’s talent, slap yourself, then listen to Nissan Altimo, on which she delivers a speed rap that could give peak Busta Rhymes a run for his money…and her word play is better.

Micky Roots

Latest posts by Micky Roots (see all)

- SINEAD O’CONNOR, THE REBEL HEART THAT BEAT IN HIP-HOP TIME — August 19, 2025

- TRUE TO THE GAME: WHY AMY TRUE IS THE ARTIST WE NEED — July 11, 2025

- REVIEW | GHETTS AT SOUTHBANK CENTRE, MASTERY IN MOTION — June 26, 2025