Credit: Amelia Lancaster

“To live is to suffer, but to survive…well…that’s to find meaning in the suffering”. This poignant, potentially timeless sentiment, overstood and expressed by many throughout human history, possibly experienced by any person, if not any being, who has ever existed, was powerfully interpreted by DMX for the Hip Hop generation on the intro to the classic Slippin’. The track delves into the tragic and triumphant details of the legend’s difficult journey, encapsulating and exploring all the pain, frustration, loss, loneliness, abandonment, rage, violence, self-destruction of being trapped in both the cycle of poverty and the ‘welfare’/ ’correctional’ system where this poverty is often at its most intense. Slippin’ is DMX and Hip Hop at their greatest; brutally honest and raw, ripping open his wounds for the world to look at and into, to see without censor some truths of the world that put them there.

Ruins, a multi-layered, multimedia collaborative production by London contemporary dance duo Fubunation is venturing into this territory, offering a fresh reinterpretation of this ancient observation for a new Hip Hop generation with a slightly different vision from the one DMX personified at his peak. The piece is at least 2 years in the making, and uses contemporary dance with a strong Hip Hop influence, sound, film, installation and photography to examine the lives and psyches of its creative directors, choreographers and performers Rhys Dennis and Waddah Sinada. Ruins is centred around the battle for and between authenticity, acceptance, respect, self-defence, strength, vulnerability and sensitivity, within and without, in an attempt to scrutinise blackness and masculinity in the creator’s experiences. It is a powerful, engrossing piece of artistic expression, that is dealing with some crucially relevant discussion points for the world we currently inhabit and the world we might hope to, especially in the African diaspora and creative communities the artists are situated in.

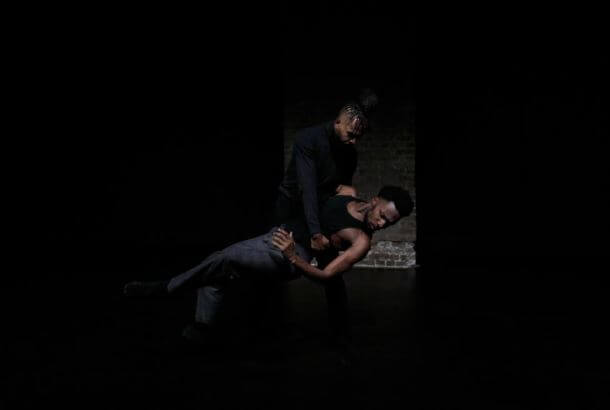

Performed this time at Camden’s Roundhouse, your first experience as a spectator is an installation consisting of cloth draped in the round with first the title, then a film projected from the centre, through the hanging material, onto the brick wall of The Hub room. The film, directed by Dennis and Sinada alongside filmmakers Donnie Sunshine and Sannchia Gaston expertly captures segments of the main dance sequence. The dancer’s bodies are wrapped, balanced and intertwined in vast empty room spaces and on bare rooftops with the London skyscape in the distance, evoking the internal and external battlegrounds – the mind and the ends – where the conflict at the centre of Ruins is played out, privately and publically. The 6 minute film and the way it is displayed add an extra dimension to the world of Ruins, meaning it can be made shareable in this digital era (alongside photographs taken by Sunshine and Amelia Lancaster), but also leaves the viewer intrigued by the ambiguity, with unanswered questions that are explored in much greater detail in the main performance.

Credit: Alessandro Castellani

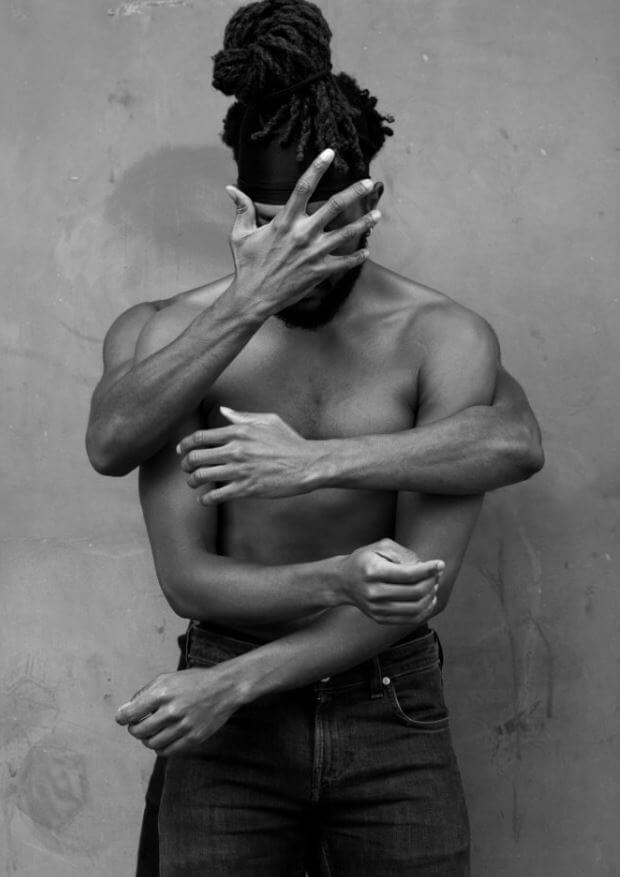

This begins with a darkened stage with what appears as a single body, barely lit at the back of the space. The body slowly moves, and you realise gradually that there are two bodies, incredibly close together. The first major movement sees the rear body place a hand entirely over the face of the one in front. This pose is held for, what for me is an uncomfortably long period of time, and is a very powerful statement. Having grown-up in the same city as Dennis and Sinada, in a similar time and community, to place your hand on another man’s face – a punch, a slap, a poke, a stroke – is generally deemed unacceptable; it is a massive statement of disrespect, insult, violence, mockery…or unwanted, uncomfortable or confusing affection. Depending on context, it would largely be met with varying degrees of reaction and consequence, and in the majority of cases would be grounds for immediate conflict. To begin this piece with such a declaration of defiance to this social norm sets the tone for what is coming in a formidable way. The piece explodes, with raw power and delicate sensitivity, into an interpersonal war between two facets of a singular entity, the inner conflict of a black man/community attempting to resolve all that they must be at once; what they are, what they are told they are, what they aspire to be, what they are forced to be, what they can never be, and all the contradictions, emotions, injuries, failures and victories that are born from this struggle.

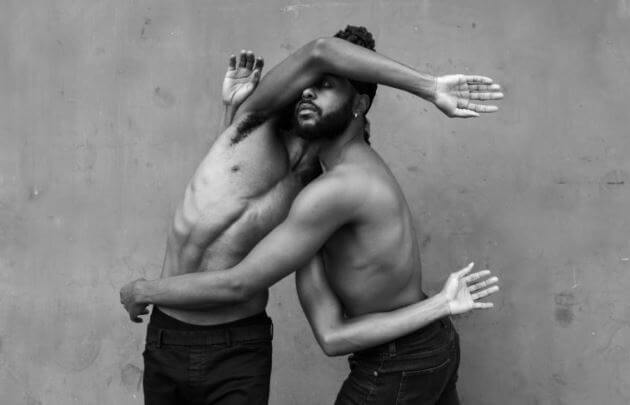

The two dancers’ bodies are rarely not touching, with their bodies interwoven, balanced, lifting, pushing, carrying, lying in/on/under/above with incredible control and a level of intimacy I personally have never seen between two black men who are not fighting, either on road or in a boxing ring or MMA cage. And yet it is a fight, an ongoing beef between different sections of the self; the inner-battle raging from childhood between the want to be happy, to play, to dance, to tell someone you love them, to hold a hand, to hug your child, to cry, to let someone in and the feeling that if you did you’d be ‘soft’, and if anyone ever knew or saw that you’d be a victim, and victims don’t survive long where we come from. Because the war is not only with yourself, but also with the other, their gaze and the way black children and adults are perceived in this society by the police officer, the racist, the teacher, the coloniser, the screw, the employer who won’t hire, the parent who won’t hug you, the other black man who’s watching you or coming at you. Right now. With a shank. So that regardless of how you feel, or what you want to do with your life, you are forced to be, as Klashnekoff put it, “ever ready fi bury a guy” whether you want to or not, or risk him burying you.

Credit: Amelia Lancaster

This is a reality that I have seen played out in myself, brothers, cousins, fathers, uncles and friends throughout my life. The so-called hypermasculinity experienced and constructed by many of us to different degrees and in different manifestations, that is under the microscope so hard right now and attacked as toxic, which it often can be, that prevents us from so much relief, ease and happiness, is necessary for so many of us to make it to and through adulthood in one piece, in a society that so often views us as a threat, a burden, a target. This is expressed in incredible depth and detail by Dennis and Sinada, as they personify an array of emotions and actions, vying for the forefront of the mind and body – joyous, gassed up, fearful, broken, defiant – battling to both break free of the constraints of their socially constructed manhood and embrace it, even weaponise it, to manœuvre through their lives, through their industry, striving to attain some kind of resolution to “the never ending gun fight” the late great Prodigy said he was trapped in.

There is also an eroticism at large throughout the piece, mostly located in the tenderness of touch used to demonstrate the oneness of the dancers, and perhaps also the care they have for themselves, the individual and/or community who is the protagonist of the piece, and perhaps for each other. This subtly unveils the core of a conversation that is urgently needed in the African and Caribbean communities of the Black Atlantic and beyond, that whether people want to accept it or not, regardless of religious, cultural or other attitudes, irrespective of conspiracy theories (that may be anchored in some truth), African-origin queer people exist, and they are also going through the conflict described above, with yet more added dimensions to this inner/outer battle we are all facing in some form. Even the terminology used to categorise people in this way, alongside the racialising and gendering terms used in this piece are potentially problematic, as none of us would be facing these specific conflicts were it not for the history of colonial domination, which is the origin of these socially constructed colonial assemblages and labels, expressed using a language that is not of our ancestors. As someone who has never had to face this particular battle, I’m not in a position to comment on it in-depth, but it is something that Fubunation have courageously and commendably confronted in Ruins, which I’m sure will generate and contribute productively to this vital discussion.

Credit: Alessandro Castellani

Ruins is an absorbing, inspiring success, evidence of how powerful art can be when the focus is turned inwards and outwards, dealing with lived experience, navigating the dangers of vulnerability with sharp criticality and the skill to manifest ambitions. Fubunation have created something amazing, with the help of an incredible production team. Through choreography, cinematography, photography, lighting and the unbelievable droning, atmospheric soundscape composed by James Wilkie and Sam Nunez, an ethereal ‘other-world’ is built to analyse and express the key themes, offering audiences the opportunity to do so with them. These themes, and the clashes at the core, are of course open to interpretation; different viewers may see the piece, themselves and their own psyche and environment reflected in a different way to how I have, which perhaps is even differently to how the artists intended, but again, I think that is the power of great art, great Hip Hop and of Ruins as a production.

Fubunation’s aim is to tour Ruins throughout 2020, so be sure to look for it, and be ready for further developments, interpretations and productions by this immensely talented collective.

For more info, head to

https://www.fubunation.org/ruins