Following my presentation on Emory Douglas’s art at the “Strike The Empire Back” event on the 14th of June 2014 in Ladbroke Grove I was able to interview Emory and discuss his insights and experiences during his time as Revolutionary Artist and Minister Culture of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

So yesterday, we had an event, which was organised by the Malcolm X Movement, which is launching next year – in the summer of next year. I gave a presentation on your work during your time with the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. I wanted to interview today as a kind of follow up to the presentation.

Q. So I wanted to know – what was the role art and culture played in the Black Panther Party of Self Defense and your role as first Revolutionary Artist and then Minister of Culture.

Well the role that art and culture played in the Black Panther Party was an ongoing process and a reflection of the politics of the Black Panther Party itself, of the 10-point program and what we believed in. Also our ideology and philosophical perspectives and it also reflected the expressions and concerns of the community at a local, national, international level. So art was one that was in line with the ideology of the Black Panther Party.

Q. What made you want to join the party initially and when you did, did it affect your relationship with your family and friends. What was their reaction to you joining the Black Panther Party?

Well initially like many young people in the inner city and during that period in time, early 1960s – mid 1960s, 1966. 1964, 1965, 1966 on up until that time, I wanted to join because there was a high level of abuse – police abuse all over the country which people were aware of and there was the Civil Rights Movement going on during that time. High levels of frustration because of what was being done to civil rights marches, particularly in the south. The lynchings, the beatings, the water hosing of the marches; all those things just to thwart to have the right to basic human rights. To drink out of a water fountain that you chose to without being beaten and you see all those things projected on television and you heard about in the news and then you could see from time to time on the electronic media – you would see South Africa and what was going on in South Africa – Apartheid South Africa then and it was the same identical kinds of things, the abuses, dogs attacking the protestors and being beaten up and hosed by the water hoses, the same political things. So subconsciously in played into my mind but at the same time it was basically like many young people during that time; high level of frustration because of the police abuse and murders across the country back then as now with it always being justified.

So when the Black Panther Party came on the scene I knew that was what I wanted to be a part of but I didn’t know about it initially. I found out about the Black Panther Party when I would go to a meetings where activists invited me to a meeting to do a poster for this event that they were planning to bring Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, to the area to honour her and they said some brothers were coming over to do security. When they came over, that was Huey Newton and Bobby Seale and after that meeting they agreed to do the security for her. So after that meeting, after I decided to join, that was January 1967, 3 months after the party had already started. That was October 1966. So it was about 3 — 3 and a half months after that because it was the latter part of January when the planning of the program to bring Malcolm X’s widow to the area and so they gave me their address when I actually called Huey and Bobby. I didn’t have a car so I took the bus over from San Francisco to Oakland, connect with Huey and then from there he would take me around, show me the community. We would go by Bobby’s house and that was my first initial involvement with the Black Panther Party.

Q. At the “Strike The Empire Back” event there was a panel discussion and Akala, who’s a Hip Hop artist from over here, he talked about how imperialist propaganda is driven in to the minds of people from a very young age. So I wanted to ask you what kind of work did you and other artists in the party do to counter that propaganda aimed at young people?

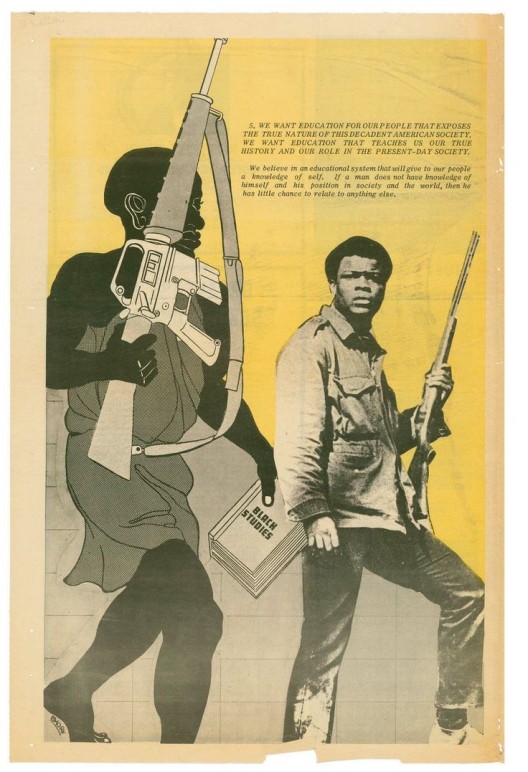

Well our art was anti-imperialist art. Our art was a reflection of our politics so it was about developing our story through the art and reflected from our perspective, from our world view and from that it was able to capture the attention of the masses who began to see what we were doing and got an alternative – another perspective that was in their interests in relationship to solving and moving forward with a movement of liberation and resistance to the oppressor at that time. We were countering it with in fact using very provocative art, very straight forward, pointing out the contradictions and not in a very snide way in most cases.

Q. Which revolutionaries would you say influenced you the most in developing your own ideology?

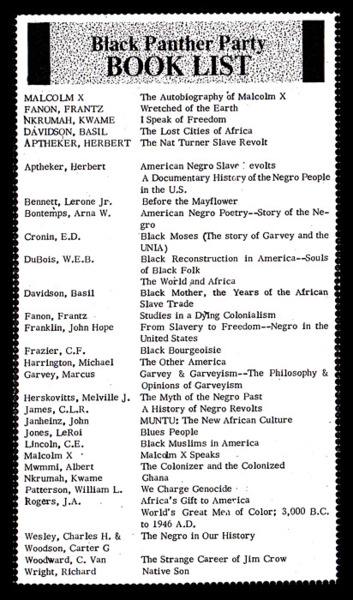

Emory: Well Huey and Bobby and them were inspired by many many aspects of what was going on in the world. It was they themselves because they were the founders and co-founders of the Black Panther Party so it was they who laid the foundations and you know they were inspired by the people’s revolutionaries and the Vietnamese and what was going on in China and different parts of the world during that time because….the African liberation movement. All those things, Patrice Lumumba, all you know the great leaders during that time. We used to read…and one of the books we used to have was the red book and a reading list, a required reading list of the Black Panther Party. Then there was Robert Williams who was an African-American who wrote the book called “Negroes With Guns” and it was one of the books Huey and them – first books they would read and sell to raise funds. There were many many many freedom…revolutions and Vietnamese — all those things – all those liberation movements and resistance movements throughout the world that were part of the inspiration for the Black Panther Party.

Q. In terms of the aesthetics of your artwork, how would you describe it and its role in propagandising the ideas of the Black Panther Party?

Well the aesthetics of it was that – tried to reflect the people and the common average everyday people in the artwork itself. We talk about the everyday with the caricatures — one that took the people on the stage and made them the heroes of themselves in the artwork therefore they became on stage the heroes in the artwork itself. They could identify with that in many ways because they could identify with there being a presence of family or someone like that and so it became an inspiration – to look forward to seeing the images during that time. I think we also we defined the nature of the pigs, the police, in American culture. Seeing them as very low down nasty creatures, with blood and filth and slop and the whole business. Of course, that may not be the case in other cultures but that was the way it was defined here. So that’s how Huey and Bobby, particularly Huey came up with the idea at that time to do the caricatures of the pigs.

Q. The Black Panther Party sought to internationalise the cause of African-Americans and also connect them to the rest of the African Diaspora. Why do you think anti-imperialist internationalism and Pan-Africanism is so important?

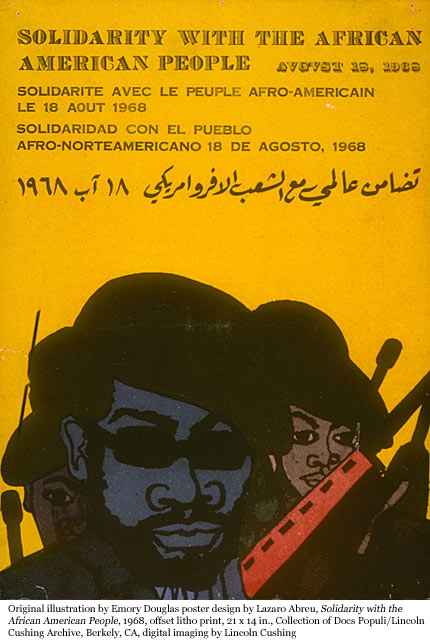

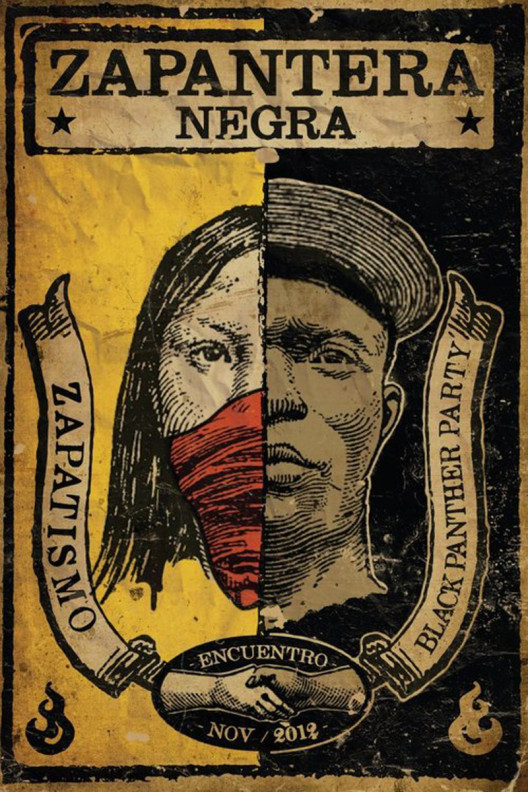

Well it was important to us because it was a world struggle. We understood that back then and that it was part of the ongoing development of ideological-philosophical perspective and knowing that the world was interconnected and that you could get anywhere in the world just in 20 minutes so it was more like a news read than it was just separation. The position at that time was about framing the co-dependence and the dependence of each community around the world of each other for survival in many ways. So therefore, the repression and the oppression that was taking place, it was always understood to be deplorable of the people’s basic human rights who were violated around the world – in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America. So that was an important part of the Black Panther Party in showing that solidarity.

Q. You also worked with artists from OSPAAAL, The Organisation of Solidarity With Africa, Asia and Latin America. How did this relationship come about and what did you learn during your time while working with those artists?

Well basically I didn’t work directly with them. Our newspaper would came out, a consistent paper. Our first paper was April 2nd of 1967 and there after I’d say in the beginning it came out very sporadically but there was very great excitement behind this paper because here you have a young organisation of young people who put out a paper, a revolutionary paper. You had liberation movements from all around the world who took the newspaper and Cuba was one of them. So what happened is they used to remix them with the images that I did and send them back out into the world in solidarity with the people’s struggle around the world. So in that context we were in linked together by our solidarity in relationship to fighting against the oppression that was going on around the world in our very different ways. So that was the connection, not that of one directly working with them in any way that what would be considered a formal way but in a more like indirect informal way where they would see art that I’d done in the paper and they would remix them into posters and redesign them and send them out to the world. We used to get them in the newspaper back in the day. We used to get them in the mail and stuff like that so it was a good thing then; it wasn’t like plagiarising because it was solidarity in the context of the struggle and highlighting the contradictions in the struggle and sharing those kinds of images. So in that connection the artwork was linked and there was that connection.

Q. Could you name some of the artists that have influenced you the most?

Well I was influenced more not by artists but more by revolutionary art of that time like the political art that came out of Vietnam and Cuba, amazing political posters by — Tri-Continental posters, OSPAAAL posters out of Cuba. And the artwork you would see coming out of revolutionary Vietnam, China, Russia and all folks that were attributed around that time kind of caught – captured my attention particularly the Cuban ones and the Vietnamese ones during that time. Also, some of the art I used to see from time to time here dealt with the anti-war and stuff like that. But I need to say as a youngster I was intrigued by a black artist named Charles White because during that time I didn’t come up in an environment where there was a lot of black art. Maybe I would have been different if I lived on the east coast – Harlem Renaissance – in Harlem where you had revolutionary culture inside in the south what have you. Being on the west coast and my mother being legally blind, I wasn’t brought up with a lot of – exposed to a lot of art but I used to go my auntie’s house and each year she used to get this calendar from her insurance company which had this calendar and they used to have this black art each year on these calendars. She had it in her house and it was the artwork of Charles White and I think that kind of impacted me subconsciously in a way in relationship to artwork itself because I always used to look forward to seeing those calendars and I always used to look at the calendars all the time. He became well known through his artwork as well.

Q. Can you talk about a bit about your time in Algeria when you were invited to the Pan-African Cultural Festival as part of a delegation of the Black Panther Party?

Yes, well I was travelling with Kathleen Cleaver there to connect with Eldridge Cleaver who was coming from Cuba to Algeria to establish his residency there and from there we were asked to be a part of the first Pan-African Culture Festival in Algeria and so we were offered to be a part of the African-American delegation that was coming from the United States and they gave us a lot on the main avenue where we could display material and artwork and since no other delegation from the United States – basically just came and had nothing to put any kind of items or materials to put into the building lot that they gave us then we began to bring tons and tons of newspapers, posters, artwork and all these things and display them and give them out to the people who came from all over the world during that time to that festival. And so that was a great experience. We were given spaces for talent – art and culture — as well as Eldridge Cleaver and Kathleen Cleaver and then Kwame Ture – Stokely Carmichael as he was known then also was there, many many people. We had musicians, Archie Shepp, all kinds of folk. Maya Angelou, many many African-Americans from a part of that sector but we are able to capture the attention because of the representation of the police force but also the fact that we were able to bring our own material which we could print at this time. Our newspaper, our posters, we couldn’t print our newspapers so we got them printed. We brought thousands and thousands of news preps, tons of paper, newspapers and posters to give away. We just gave it away. So that was a great experience in relationship to sharing and inseminating what we were about to people from all over the world. And we used to meet with African liberation movements and we would document when used to meet with the African liberation movements while we were there in Algeria.

Q. Since the Black Panther Party was violently dismantled by the state, what work have you been involved in since and what kind of work are involved in at the moment?

Well, I’m still involved in all artwork that deals with resistance and exposing human rights – violations in relationship to human rights and the community and I feel that is reflected in my artwork and that’s an ongoing process. For many years though prior to that there were always some space from up into the 80s into the 90s – late 80s mid 90s – for me to do presentations but of course I had to focus on things that were in front of me. I had family so you know, I had Eldridge so I had to take care of that for about 13⁄14 years up until 2004/2005 before I began to really do a lot of travelling for presentations with the artwork. There has been a lot of interest still in the artwork itself and also people wanted to know what I had been doing so they really had the chance to see some of the art that I had done since the Black Panther Party up until recently.

Q. What advice would you give to young revolutionary artists?

Well to be a revolutionary artist you need to have basic knowledge of what it is you reflect in your art — the cultural projections that you are sharing with the world. You have to be knowledgeable and integrate that into your art. You have to have strong convictions, be able to defend what you believe and what you say and be able to communicate it in a way that even a child can understand it — if he can most of the time — and you have to be able to be on principle. Not to do it just because it’s the cool thing to do, you know like it’s a fad. It’s an art. It’s a life. Plan it. You have to understand that you basically — artists a lot of the time stop being artists because they think they want to make money so they stop being artists but they want to get a job. But at the same time you ain’t necessarily gonna get rich doing progressive revolutionary artwork. So you have to enjoy yourself, have fun to as you’re doing it knowing that it’s an ongoing struggle and that and that you have to have strong convictions over what you do. Basically be insightful and evaluating things that you see and doing work that’s always in solidarity with the oppressed people around the world.

Dhruv Shah

Latest posts by Dhruv Shah (see all)

- Review: Iron Braydz (@braydz) “Verbal sWARdz” EP Unorthostract Records — May 8, 2015

- Interview With Revolutionary Artist Emory Douglas — January 20, 2015