There are some films that needed to be made. When you watch them, there can be many effects. One is that of a harmonisation that you didn’t know was missing, a filling in of a hole in your cultural landscape that, now present, resonates in a way that makes it feel more complete than it had before. This was my experience watching “Black is Beautiful: The Kwame Brathwaite Story”, a poignant, vibrant documentary directed by Yemi Bamiro, shedding new light on the life of a master Pan-African artist and the family and community whose reciprocal love fostered and fuelled his incredible life’s work.

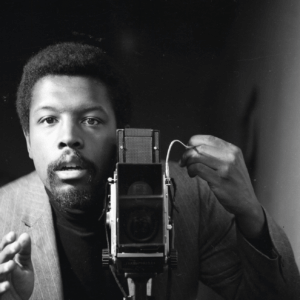

Kwame Brathwaite, his wife Sikolo and his brother Elombe are pioneers of the Black is Beautiful movement, the conscious and deliberate campaign initiated in the 1950’s to encourage people of African origin to be proud of our heritage, our deep cultural and Spiritual history and the physical features it endows us with. Born out of the growing Pan-African revolutionary ideals that were reshaping the minds and lives of African people across the world, through their practice of art as politics embodied in their African Jazz Art Society & Studio (AJASS) and Grandassa Models organisations, the Brathwaite’s and their wider community were a driving force behind the movement. As Bamiro documents beautifully, they coined the slogan ‘Black is Beautiful’, living the principles, sinking it into every act of creativity and mobilisation they undertook, from Kwame’s stunning photography to their contributions towards liberating African nations with multiple forms of support.

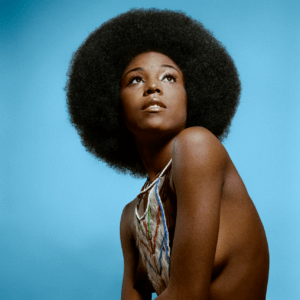

70 years of impact by the movement can make it easy to take it for granted just how huge a shift in thinking this idea was in the mid-20th century. 400 years of calculated Afrophobic racist conditioning had taken devastating hold on many societies, including in the USA. The affiliation of whiteness with not only beauty, but cleanliness, righteousness and divinity and Blackness with all the opposites, created a deep seated, internalised racism within individuals and communities. As Brenda Evans, an original Grandassa model expresses in the film, her mother told her “when you see me in the street, don’t talk to me”, if she chose to wear her hair as it grew naturally, and wasn’t straightened. The film portrays the early resistance that even communities like Harlem had to the movement’s afros, African aesthetics and clothing and appreciation of dark skin, as Black people came out to protest against the events of unapologetic African pride, celebrating African ethnicity and Black beauty.

Over decades, the movement spread nationally and internationally, was co-opted by capitalism, but ultimately became so successful it changes the world, transforming with how Black people see ourselves, our bodies, our Ancestry and our place in our societies, to the point that the mantra Black is Beautiful become so wide reaching, so accepted and popularised that the Brathwaite’s and their roles were absorbed to the extent they are almost written out of the story.

With an amazing cast of the Brathwaite’s family, friends, collaborators, archivists and collectors of Kwame’s works, Bamiro and his team build on the archival work of Kwame and Sikolo children and historian Tanisha Ford, following the family’s journey of unearthing Kwame’s art and bringing the Brathwaite’s legacy to the fore, building outwards from Kwame’s photography. Speaking with Bamiro before the film’s première at the BFI London, he spoke of the “overriding feeling of gratitude and privilege” he felt to get to work on such an important piece of history, being “the custodian” of a precious and fragile story that had been a whispered and not shouted part of the Black Liberation struggle, so required careful handling. With intricate care and a delicate intimacy, Bamiro and his team gave “a nod to Kwame’s aesthetic” in the how they crafted the film, picking locations “that felt like locations that he would have shot his subjects in”. They stayed in Harlem for stretches of the production, soaking up the energy of the Brathwaite’s home for so long, that is still a central hub of African American creativity.

This intimacy and care are tangible in the documentary, something Bamiro intended and achieved. He has crafted a work that he considers to be a love story, a love that the Brathwaite’s had for their people, but “ultimately a love story between Kwame and Sikolo… always felt about one man’s love for his woman.” One of Bamiro’s major takeaways from production is that Kwame “…loved his people, he loved Black women, he loved Black men, he wanted Black people to love themselves. He took it on himself to be the messenger of that…but the love he had for Sikolo was the thing. Black women are co-curators of the Black is Beautiful movement…if it wasn’t for Black Women, I don’t know if you’d have a Black is Beautiful movement in the way that you had it. He pedestalled those women and he showcased them, but they also had agency over their own selves. Him and Elombe just helped them along.”

“Love is at the heart of all of this…and I think you see that through the legacy of love through what Kwame Jr and Robynn have done with the archive, you know? It’s not an easy thing to do, to take on that work and to promote it in that way; they have three children, they have jobs, but to put that at the centre of their world is that love for their father, and their father-in-law. Love is at the heart of all of this one. Love is a central thing”.

One of the other core themes woven through the film is Kwame Brathwaite’s ability to simultaneously live his art and politics. The film captures the inseparability of the two as his life’s work. While the Black is Beautiful movement was inherently political, it was born out of the Brathwaite’s Pan-African worldview. The brothers made constant contributions to African liberation, from sending material support to numerous liberation movements, to hosting revolutionaries in New York, to travelling to Africa and documenting the waves of change. There is an exquisite scene where Kwame Jr. tells of his love for his father’s checklist of liberated African nations, which really spoke to the dedication he had to the liberation of African people all over the world, and how his art was one of the many ways he found to play his part. Bamiro reflects on this are powerful:

“He was just a man that lived many lives. He died when he was he was 85 years old; when you look at his life and all the things that he did and all the different hats that he wore , It wasn’t just the stuff, the celebrity stuff, It wasn’t just the stuff in the Apollo. It wasn’t just the stuff in Africa. It wasn’t just the stuff of like normal black people on the street in Harlem. It wasn’t just the album covers. He found a way to continue to e promote us, pedestal us, but then also find this creative satisfaction from every hat that he wore….That is just such an amazing thing to do over the course of 85 years of your life. To have a life that full, that you made that much of a contribution, you did that much. It’s just incredible. He didn’t waste any time”.

The film is a sequence of wonderful realisations and lessons. One, which was part of one of both mine and Bamiro’s favourite scenes, was the speech Nelson Mandela gave in Harlem after becoming leader of post-apartheid South Africa. I had no idea this had happened; like many aspects of Kwame Brathwaite’s life and career, he and Elombe has facilitated it, in their typically understated and humble way. I had been raised on the affirmation that Black is Beautiful, had of heard Kwame Braitjwaite’s name and seen some of his work, but until seeing this film I was not aware of how prolific he was, how central he and his family were to several massive movements, just how influential he had been and continues to be, or how underappreciate he had been for so long. The gratitude I feel in now being aware of all of this is testament to both the powerful legacy of the Brathwaite’s and to Bamiro’s filmmaking. This film deserves all the great success that I’m sure it will receive.

Apex Zero

Latest posts by Apex Zero (see all)

- REVIEW | BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL: THE KWAME BRATHWAITE STORY [FILM] IN COVERVASTION WITH YEMI BAMIRO — October 20, 2025

- EVENT | SPOKEN FUTURISM LIVE — OCT 2–4 2025 — September 25, 2025

- END OF THE WEAK MC CHALLENGE WORLD FINALS HEADED TO UGANDA, AFRICA — May 29, 2025