How did you and DAM begin?

I started solo before DAM and then Suhel and Mahmood came along and we formed DAM, but I did solo shows a year before that.

So then how did the formation of DAM come about?

It’s a small city. You don’t need to be the first rapper there so that everybody can hear about you, it’s enough that you listen to hip-hop and people will think that’s rare. Talking about before Ja Rule, way before Eminem; no white skin was doing hip-hop. I was that guy that was playing it in the car, burning CD’s for the people. I used to sit with my friends and this is how I studied English; I used to translate the lyrics and translate to my friends as well.

I’m coming from the biggest drug market in the Middle East [Lyd, a city in Israel] so it’s obviously dragged them in enough to say “Fuck the police” and they’ll like it. I’m visiting my brother in prison who liked it. So that’s when I started at the beginning, but then I decided to release an EP in English because that’s what I heard; I’d never heard anything but English in rap. I did a small party in my house and I invited my friends. One of my friends asked if she can bring her young brother, and he came and he said “I like hiphop, I also like rapping” and so we had the idea to form DAM.

And the younger brother was who?

Well Suhel, my brother, was already with me on stage and he was filming stuff because he’s more into the cinema world. And then the third was Mahmood who came; he used to be my friend’s brother and now he’s my wife’s brother; she became my wife. Me and her were friends forever and she just brought him to that party where we met and he showed me how much he loves hip-hop and we started DAM.

I’ve noticed that every time we played the songs to people, I’d lose their attention like a minute after and that’s when I started working on Arabic; they didn’t get the lyrics [in English] it’s not my crowd. I heard that there was this Israeli hip-hop scene and I went there and it was way more developed. It was very developed. They were doing it in Hebrew, they had the techniques. They had the flows, the rhymes. It just shocked me and I started doing it in Hebrew and developing Arabic.

So you started first in Hebrew and then in Arabic?

First English, second Hebrew then Arabic. But it went international and very big, and went to the levels of being a superstar in Palestine when I released the first Arabic single. This was solo, before DAM.

Where? All of this happened in your hometown of Lyd?

Nah, it’s bigger than Lyd. It’s mostly Haifa; the North is more advanced culture-wise. The centre and the south are more poor so the culture and these things are more in Haifa, in Nazareth; they have theatres. Even up ‘til today I did like fifty shows in London, 70 shows in New York, and maybe three shows in my city Lyd. It’s a hard place but we are developing it.

When you’re away from your homeland, do you feel that other people define you by what their idea of being Palestinian is?

Ah, no but they have expectations that I don’t like to follow sometimes; they just have expectations.

In what sense?

Like that’s my issue; that’s my thing. And it makes you feel that you have no… like it’s challenging because you wanna prove you are not a geographical talent. I’m not a rapper or have good punch-lines just because I was born in Palestine. That’s something I added; Palestinian hiphop is something I added to Palestine. It just makes you feel that all they wanna hear about is the cause and these things. I think Nina Simone had that same thing because she was an amazing singer but as soon as she did “Mississippi Goddam”, then suddenly she became that thing for the struggle, and when she tried to come back to other songs people just wanted to you know.

Yeah, but I’m trying to break through. My last four singles in Arabic, I think they were very entertaining and very dance, and they are being played in clubs like a good mainstream song and I’m enjoying that cause for me to do a mainstream song, a commercial mainstream song, is also something that’s resistance and revolutionary because they boxed me into this “the political rapper”. I’m not talking about “suck my dick”, “show me your tits”. Musically, the way people approach the song or they play it and they dance to it, I think this is something that I’ve been able to do for the last four or five years. For me, it’s resistance. For me, I just wanna show that I’m an artist; I’m not just a geographical product.

So even if you’re not necessarily talking about the resistance, the song that you’re making is within itself an act of resistance.

If you go to my Palestinian fans, they will quote political songs, but they will quote also the fun songs. But when it comes to Western media that’s it for them, it’s just “he’s from Palestine.” But for example, if they wanna interview Jay‑Z, they will be interested in his new work, his new art, his latest things; on “4:44”. But for us, I cannot remember one Western interview where they didn’t ask about “Who’s the terrorist?” which is something we released in 2001, but it’s a political song and we have thousands of songs that are not political. I can understand it but sometimes it pisses me off and I feel that it’s stereotypical. So are you telling me that in the case that Palestine is free, that means that there are no talented people over there?

They should see the occupation as a border for us to get into the world, and not something that we need to feed our art because I would fucking love it to write a full love album. I would love that and the only thing that’s annoying me in a way, to go full LL Cool J, as an example. It’s just annoying that they don’t come and they do an interview where they ask me about a certain line. It’s “So, how is Palestine? What do you think about what happened?” Ok, in the crowd you have like three hundred Palestinians, go and talk to them about Palestine; there is nothing special about me. But study my lyrics, ask me about the hook. How come this bass-line is this? They never go there.

In most cases, I don’t think that people know anything about Palestine that is beyond the struggle. We have people that die from cancer. We have people that have alcoholism. We have people that drink only one glass of wine a day. It’s just like every other society, and yes we have that fucking occupation.

But it’s not everything that you are?

Most definitely not.

So I hope it doesn’t annoy you to ask this now, but my favourite song is لو أرجع بالزمن (If I Could Go Back in Time). I’m wondering, how did you come to this idea, and then of doing the song backwards?

We didn’t invent the wheel. Nas did it. He did it in “Rewind” [from Stillmatic] but he didn’t do it about honour killings.

So when there’s a crime, there’s an investigation. And when an investigator wants to investigate, he goes to the scene. He goes backwards and he tries to understand what led to that. But when it comes to women, there is no investigations. A guy killed his sister, and it’s like oh, probably sharmoota [derogatory term meaning whore] she probably slept with someone. So they don’t investigate. Like when an Israeli soldier just shoots a guy in Gaza, there are no investigations; he probably threw a stone, probably a terrorist. That’s it. The case is already closed before the crime and this is it with women. I decided to go in like an investigator, to go backwards; to go to the crime scene. That’s why it starts with the line “Before she was murdered, she wasn’t alive.” So we went back; the bullet comes out of her head, we go back to the house… it’s like an investigation. And I wanted to deliver the message of it’s a crime, just investigate it and don’t just say “Because she’s a woman, that’s it. We don’t investigate it. He probably had a right to do it.”

It’s like having liberals. For example, there was these Israeli snipers on the border of Gaza who shot a guy and they started laughing. The right wing people started saying “he probably had a gun” and you can see that he doesn’t have a gun. Maybe he had a stone but between him and the soldiers, there’s two miles. He’s not a threat and he’s behind a wall. You don’t kill that guy. The liberals got pissed off because why do you celebrate his death? You don’t have to celebrate his death. They are missing the fucking point; you killed and innocent man in a way.

So this is it when it comes to women. Some might say, “yeah, she probably had sex with someone”, some might say “you cannot know, but I don’t know, maybe she provoked him” That’s the liberal. Let’s just check it; was she killed because she had sex? I had plenty of sex, you wanna kill me as well? And then we go all the way back to the day she was born, and this is where we found that she is guilty; as soon as the doctor said she was born a girl. And that’s “you are guilty until you are proven”.

I treat the woman issue in the same way; I want to take responsibility in the same way I want the occupation to take responsibility for what they did to me. Look at the occupation. I want you to apologise, I want to do this and this and this; this is how I feel. And I go to the women and ya3ni, maybe it’s not 100% comparable but that’s how I think of it.

Well it’s oppression; and oppression is oppression no matter what.

Yeah, but this time I’m the oppressor. So it’s different.

But it is the issue of suffering at its core. It’s unusual for me to hear a brown man talk about women’s rights. It’s not something that we see generally, but especially when it comes to men of colour.

Nizar Qabbani [Syrian Poet] did it. Mahmoud Darwish [Palestinian Poet] did it. I challenged him too; there’s a line that I really like. He talks about how we will become a nation and we don’t have to carry Palestine on our backs the whole time. One of the lines is, we will become a nation when a poet can describe a female’s body in an erotic way.

I took that line and I challenged him saying “May he rest in peace, but I think we will become a nation when a woman can describe a man’s body in an erotic way.” in the song “Ye Reit” from the Junction 48 soundtrack. The feminist basics are there. I’m sure my son, or someone else’s will hear the line and take it further. Maybe he will give it a third twist about the LGBT for example. I don’t know.

To build on the work that’s already been done?

Yeah, adding to it.

What do think at this point the future looks like for DAM and also for you?

It looks amazing. DAM just signed with Cooking Vinyl, and the album is more than 80% ready. It looks like we’re gonna release it in January. I hope so, Insha’Allah. It sounds fresh and I’m fucking enjoying every work with it. Cooking Vinyl is an amazing company and they’re taking good care of us. They’re based here in London. DAM has a fresh sound now because Maysa is an official member. She started as a singer with us on stage, she’d do the hooks but now she’s literally in the studio with us, cooking with us, so it’s her melodies, her lyrics, and she’s doing rap as well, she’s singing the hooks; we’re singing.

It’s just very very interesting the way it’s being cooked, and it’s very interesting because the musician working with us, Itamar Ziegler, doesn’t understand Arabic. He did the soundtrack of “Junction 48”. He’s an amazing talented dude, and the thing is with him, he doesn’t understand the lyrics right? Of course he understands the concept but he doesn’t understand each line because he’s a poetry guy as well, so he really cares about the metaphors, about the allegories. But what makes it a very hard process but very productive and unique is that I write a verse, Maysa has a verse, Mahmood has a verse. I go and I start spitting and on the third line he’s like “Ok, stop. I want Maysa to come in now.” It’s like but dude, doesn’t make sense lyrically. “I don’t care. Change it.” So you force yourself to change it because musically it would sound more fresh if she came in after a bar and a half. And then she comes in and he’s like “Ok, ok stop. Bar and a half. Come back do words.”

And you just start writing again and re-writing again and it’s very hard and it’s frustrating and you just wanna punch him. But when you listen to it your like damn, that’s fucking fresh.

Because he understands the concepts.

Yeah. It’s so hard when you’re an emcee, you’re really in to the lyrics; you think that every lyric is a part of your body. Like if he takes one line that means he just cut your finger from your body and it’s painful, but when you listen to it and you see the way it’s shaped and it’s beautiful it’s like “Dude, he just made my nails; he didn’t cut anything, just my nails… look how beautiful they are.” That’s what he did.

I worked with Udi [Aloni – Director of Junction 48], and he’s an amazing mentor for me. For the last three years I’ve learned something, I’ve learned, for me at least, the essence of writing. I don’t waste my time on finding a way to write good; I use my time on knowing what to delete. That’s the advice for me, that’s how I work. I’m trying to develop a talent where I can know what to delete and what to edit.

To be selective?

Yes. Yes. It’s very hard. It is very hard. And I learned that I do it, but it’s better if I give it to someone else. And I still have that thing where I send it to him and he’s like “Let’s delete that line.” And I’m like “Are you fucking crazy!? It’s an amazing line! And we remove that line it’s gonna fuck up another line, and it doesn’t make sense!” And he’s like, “Just fucking delete it.” And then I delete it, and then I record it. First time I hear it, it makes sense but I will not admit it. After five or six times, I’m like “Whatever man, do whatever you want.” So it’s very hard ya3ni, bas it’s an amazing process. For me, hiphop is based on sixteen bars. For me to deliver a message in four bars; I wanna do it once in my life. But actually that’s the hook.

Take a Drake song for example, “God’s Plan”, I don’t know the song; I heard it once. But I always repeat “She say, “Do you love me?” I tell her, “Only partly” I only love my bed and my momma, I’m sorry.” It’s stupid but the way it’s done, the way it’s said, the way it’s planted there; it’s like a hook but it’s not a hook, it’s a verse. But people no longer sing hooks in hiphop and that’s it, they sing a few lines and it’s like a hidden hook inside. To plant these things, this is what we call a “textual tattoo”.

Like if you take that Neptunes tune with Jay‑Z. Go to a club, everybody, even people who don’t like hiphop; they’re gonna sing the hook because the hook is there. But they will also sing a few lines. Like everybody in the club will say these two lines; “And I wish I never met her at all”. People who don’t like hiphop will repeat these lines. And it’s art, I know it’s commercial and I know that people who come from the KRS [One] era, and coming from Mos Def and Talib Kweli; they look at Drake and these people like this. But I think it’s art.

And it’s still part of the culture.

Yeah. And I want to be an entertainer, not just the guy who wants to say something. C’mon, if I come to a Drake show, I want Drake to tell me something new, to freshen my politics. I want him to take a side against guns. But I also wanna dance. If I go to a KRS-One show for example, a Dead Prez show for example; yes I know I’m gonna get something about Palestine, about the US but give me something to Dance to aswell. Give me something to have sex to. I deserve that; I’m not coming to a lecture. And that’s what I’m trying to take; it’s why I cannot hate on Drake; you can learn so much from these guys.

So I write lines and I record it, then I delete stuff. Then I play it to people who understand the lyrics. And I stop it and I ask them “Do you remember one line?” And if they don’t remember any line then I go back. That’s how I started and now it’s very easy for me to do it. Now, I feel that people leave the show and they listen to a song one time; they already have lines in their heads. If a guy picks a line and is like “Yeah, I like that. I think of that line.” Then I’m going to mute the drums and keep that prize. It’s a process. It’s a fun fun fun process. Nobody asked for my advice, but it’s very cool to give somebody who doesn’t understand the language a listen to it, and see when you lose him.

Like if you listen to Saian Supa Crew. A French collective; like seven emcees on one stage. Back when Eminem released “The Marshall Mathers LP”; he was number one in all the world except France, he was number two because they were number one in France. These guys are… you can listen to their whole album, I don’t understand French but they are beyond emcee’s; they are musicians. You can see that there’s some spark.

I’m working on an English/Arabic album now. I’m gaining confidence. I’m enjoying this process. I’m doing it here in English and then I’m going back to the studio with them to do it in Arabic. It’s a cultural jetlag for me to move from the Arabic language; it’s like flying from Palestine to the US, you have that jetlag. It’s becoming easier and easier and fun.

Now for a few lighter questions…

Who are the rappers that have stayed with you from the beginning to today that you still appreciate, listen to and study?

Tupac.

Kanye. I know he’s a douchebag sometimes, fuck that Trump shit.

There was a point where I was sick of hiphop; I felt that it had amazing singles but shitty albums that don’t carry. I just got bored, and you know when I realised that I mostly appreciate Kanye? For me, he’s not the best rapper, but when I moved out of my house I noticed that I had one album of this and that, and I noticed I had all of Kanye’s albums. I brought each one of them. And it took me time to understand which one I liked most because every one is different. He is searching; I enjoyed his music. And fuck what said about Trump, and the shitty things that he says, and the capitalism that he’s trying to promote. But I cannot lie that my heart skipped a beat when I heard that he’s dropping four albums in one month, so I cannot say fuck Kanye.

I enjoy Kendrick. I feel sometimes it’s too much but I enjoy him. What he did on the Black Panther soundtrack is fucking amazing.

I really enjoy J.Cole. J. Cole has songs that I will carry for fucking ever. Songs like “Lights Please”, songs like “Wet Dreams”. “Lights Please” taught me a lot. It’s a song about sex but it has politics in it.

This guy whose name I cannot pronounce. That’s the guy who I’ve been listening to mostly for the last three/four months. I cannot stop. XXXTentacion is his name.

Nipsey Hussle is fun. If you miss West Coast stuff; he reminds me of when The Game came out.

Rhapsody. She is fucking amazing. She is very good.

What are your favourite words?

I hate the word literally; because I cannot pronounce that word it’s pissing me off (he pronounces it literately)

I love words with the letter R. I love the R because I think my R as a Middle Eastern is special. I just comes good. It rolls and I like it. It makes me feel like I’m starting a Ferrari or something. Maybe to some people it sounds like a kitty purring.

It can be either.

Both are good. A pussycat driving a Ferrari; that’ll be the name of my album.

Shukran Tamer.

Blessings.

Listen to Tamer’s latest song “Johnnie Mashi” here

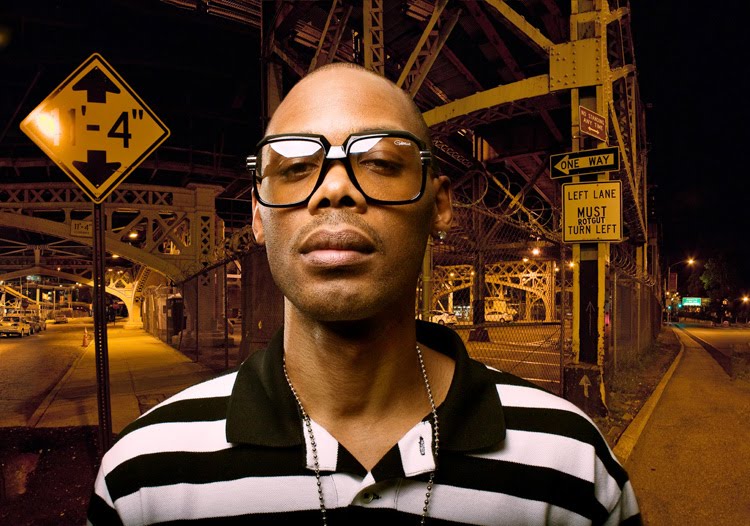

Add Tamer on Social Media

Instagram — @tamerdam

Facebook – Tamer Nafar

Aisha

Latest posts by Aisha (see all)

- INTERVIEW | 47SOUL INTRODUCE US TO THE SOUNDS OF ELECTRO ARABIC DABKE — October 18, 2019

- INTERVIEW | ASIM QURESHI — AUTHOR OF “A VIRTUE OF DISOBEDIENCE” & DR. LAYLA HADJ – MANAGING DIRECTOR OF CAGE — February 19, 2019

- REVIEW | “A VIRTUE OF DISOBEDIENCE”: MUSLIMS IN TODAY’S SOCIETY — February 19, 2019